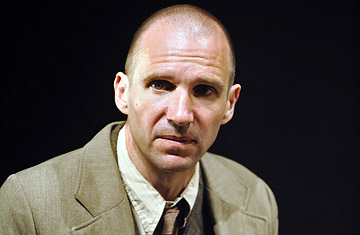

Ralph Fiennes performs in Beckett's First Love, directed by Michael Colgan.

(2 of 2)

The plays also reinforced the argument that Beckett was, in large part, a comic writer: unquestionably deadpan but characterized by (his phrase, from Happy Days) "laughing wild amidst severest woe." Godot is really a spectacle of mordant vaudeville; the role of Estragon in the first Broadway production was taken by that comic Cowardly Lion, Bert Lahr; and in a 1988 Lincoln Center revival, directed by Mike Nichols, the stars were Steve Martin and Robin Williams. The set up to the play's gag: they wait for Godot. The punch line: he doesn't show up! Maybe this is concept comedy, an essay on the deflating and the persistence of hope, but it's as comic as it is cosmic.

Laughing wild certainly abounded in the hour-long Saturday matinee of readings from Beckett texts by Fiennes, Neeson, McGovern and Julianne Moore. Among the readings was a passage from the short story "The Expelled," published, like "First Love," in 1946. Its protagonist is a dour brute not far from the nameless necrophile in "First Love," and Fiennes again took the role. He describes walking down a city street when "I had to fling myself to the ground to avoid crushing a child. He was wearing a little harness, I remember, with little bells, he must have taken himself for a pony, or a Clydesdale, why not. I would have crushed him gladly, I loathe children, and it would have been doing him a service, but I was afraid of reprisals. Everyone is a parent, that is what keeps you from hoping... They never lynch children, babies, no matter what they do they are whitewashed in advance." As Fiennes spat out this comic misanthropy, the audience let out communal barks of involuntary, sometimes chagrined giddiness, and at the end erupted in applause.

The guilt of Irish laughter resounds through much of I'll Go On, McGovern's and Gerry Dukes' selection of passages from the three novels. McGovern, one of the foremost players of Beckett, mines every vein of showmanship in the works. Riding a bicycle while holding crutches, or squatting nearly naked and spitting out whole paragraphs in a long breath, he's a veritable Cirque de Solo. Even on his deathbed (in the Malone Dies section), the McGovern-Beckett character finds much to laugh about, though his smile is a rictus.

What won Beckett his Nobel Prize — the grim death gargling at you from every page — may also keep audiences away; they think he's a sanctified chore, homework for Mensa members. But as McGovern, Fiennes and Neeson demonstrated, with their considerable artistry, Beckett was a mesmerizer, a spellbinder, who held a cracked mirror to humanity and saw the humanity in it. We're pitiable creatures, no doubt, and birth is just the first step toward death, but funny in our cruelties and yearnings. At least that's what this Beckett fan thought at the end of the Gate marathon, Laugh? I thought I'd die.