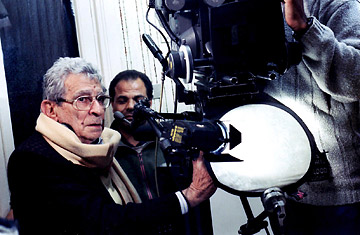

Egyptian movie director Youssef Chahine, left, standing behind a camera during the shooting of one of his movies in Cairo, Egypt.

(2 of 2)

I've searched for the truth, again and again.

I've loved so many, yet few remember me.

They're in my heart. Am I in theirs?

I stretch a loving hand — why refuse it?

Chahine loved his country, but he was the lover as critic — the kind who says she's put on a little weight and she didn't hold a free Presidential election for 24 years. Egypt loved him right back, but as a mother adores her son (like Mrs. Iselin toward Raymond in The Manchurian Candidate). When Chahine behaved well and got festival prizes, Egypt was proud; when he criticized powerful political interests, she sent him to bed without supper. His epic Once Upon a Time on the Nile, about the building of the Aswan Dam, was the first Egyptian-Soviet coproduction, but both sponsors were displeased by the director's cut, demanding reshooting and re-editing. The film, begun in 1968, was not released until 1972.

With Nasser, Sadat and Mubarek effectively playing his studio bosses, it's a miracle Chahine could get as much said in his movies as he did. One of the most sympathetic characters in Alexandria...Why is a young Jewish woman who had Hitler's Germany for British Palestine. "I thought I had escaped the Nazi inferno," she says. "Yet in Haifa I faced another." Destiny, Chahine's 1997 a bio-pic of the medieval liberal Muslim philosopher Averroes, was a forthright attack on religious fundamentalism; it begins with a burning at the stake and ends with the burning of books.

Chahine's derision toward fundamentalists goes back at least to Cairo Station, where he portrays them as comic relief: when they see dancers gyrating to rock n roll, the clerics mutter, "God protect us!" and "All these new-fangled ideas lead to Hell!" But Chahine was also a nationalist. His 1963 bio-pic Saladin, about the 12th-century sultan of Egypt and Syria, found a clear connection between Saladin's uniting of North African and Mideast Arabs against the Christian Crusaders and Nasser's formation of the Egypt-Syria United Arab Republic to fight Israel. (Saladin was played by Ahmed Mazhar, who had attended the Cairo Military Academy with Nasser and Sadat.) Several Chahine films, including The Sparrow in 1973 and the 1978 The Return of the Prodigal Son (loosely based on the Andre Gide novel), were set during the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973; there was no question which side the films were on.

His fondness for America, and his reservations about it, found their final expression in Alexandria...New York, where an old filmmaker runs into an American woman he'd loved a half-century before. Yet Chahine always made distinctions between the American people and the U.S. government. In his contribution to the 2002 omnibus film 11'09"01: September 11, shown at the Toronto Film Festival on the first anniversary of the World Trade Center attacks, he floats the argument that Islamic militants had the right to kill civilians in the U.S. and Israel — because these are democracies, where the people choose their leaders and thus are responsible for policies that enslave the rest of the world. The hand he stretched out here meant to slap the politicians but instead hit the mourning citizens of the country whose movies had taught him so much.

The problem with considering Chahine's career is that, just when you feel he deserves a good spanking, his movies play the cunning jester, and all is forgiven. Destiny, though its beginning and ending are literally incendiary, is at heart a ripping yarn with much buckling of swashes, and musical numbers, too. The Other, a hit at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival (where Chahine received a 50th Anniversary life-achievement award) and at the Toronto and New York fests, is a delirious blast — a politico-romantic amalgam of melodrama and music, at a pace and pitch that Bollywood directors wouldn't dare dream of.

In fact, it's a shame Chahine's work isn't familiar in this benighted part of the movie world. He was no minimalist Sphinx; he believed less was never enough. Embracing a splashy masala of styles, he threw everything — ideas, people, whole nations and regions — up in the air for the viewer to try to catch. And beyond his movies' entertainment value, it wouldn't hurt for Americans to see the visions of a cosmopolitan filmmaker from the Arab world, who speaks for himself but reflects the dreams and fears of a people whose popular culture is nearly unknown in the U.S. In the lyrics from that song in An Egyptian Story we hear, in all their naked emotion, the national fervor and questing heart of Youssef Chahine.

Your name matters little, nor where you dwell.

Your color matters little, nor your origin.

I love human beings, wherever they come from.

O, oppressed brother, hear my cry! A cry from Egypt.

O, oppressed brother, hear my cry! A cry from Egypt.