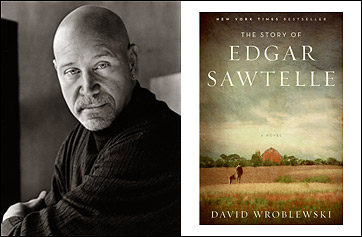

Author David Wroblewski and The Story of Edgar Sawtelle

Lawyers have been best-selling novelists, and doctors and even architects. But you don't find many tech guys dominating the fiction best-seller's list. Even David Wroblewski, author of what's shaping up to be the sleeper hit of the summer, The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, and a veteran computer programmer, can't name any. "I'm a little surprised that it's so hard to think of at least one other example," he says, noting that the impulse to write fiction is hardly uncommon among people used to writing in code. "I've run into lots and lots of people in the software world who say, 'Yeah I used to write in college and have a novel in the drawer at home.'"

With Sawtelle now at number 6 on the New York Times Bestseller's List (and number 2 on Amazon), Wroblewski, a veteran programmer, may be the first software dude to hit it big. (And with a debut novel, at that.) The book itself has absolutely nothing to do with technology — it's a Hamlet-like tale about a mute boy who raises a special (and fictional) breed of dogs on a farm in Wisconsin. Yet Wroblewski says that being a software writer helped him craft the novel and gave him some insight into the mechanics of breaking down the project into manageable components, and seeing it through.

Wroblewski, who himself grew up on a farm in Wisconsin, initially wanted to be an actor. But he fell in love with tech when he got hold of an employer's TRS-80 Radio Shack computer in 1978, and wrote a tiny routine for it. (It wrote out the lines to Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken, accompanied by blinking pixels.) "It was a gigantic, eye-opening experience for me," he says. "My first experience of software was literary and it really spun me around. The connection fell into place pretty fast for me: You can do fun stuff on computers."

For the next decade or so, Wroblewski, 48, worked full time as a developer for such companies as Honeywell, where he toiled in the avionics division, writing code for a gyroscope with no moving parts; and MCC, in Austin, Texas, the nation's first computer research consortium, where he worked in the natural language processing group on AI. How many best-selling novelists can you name with a patent? He's one of three guys who were awarded Patent 5,339,391 for "Computer Display Unit with Attribute-Enhanced Scroll Bar." (If you'd like more evidence of his geek bona fides, see his resume on LinkedIn.)

For reasons that elude him to this day, Wroblewski says he got interested in fiction writing around 1990, and began taking creative-writing workshops. Gradually, he got the idea for Sawtelle and enrolled in an MFA program that allowed him to work, mainly, from his home in Colorado. Why pursue an MFA? Because he as an engineer, he was vexed by the structure of narrative fiction. He was especially interested in what he called "middle structure" — "at the bottom level of a novel are sentences and scenes and paragraphs," he says. "Tiny particles of the story. At the top level is the easy-to-summarize plot — it's got some twist, a climax and a denouement." But at the middle level, he says, when you look at a book, chapter by chapter, "you don't get any guidance at all. What keeps you going?" Wroblewski says that the middle level of narrative is the trickiest part to parse, from an engineering perspective, because it's murkier and harder to define. What impels a reader to read on? "It can't be drama," he says, "because what is drama?"

It was a fascinating problem for a software engineer. "In the software world, we have elaborate, elaborate software mechanisms for handling structure. Think of Object Oriented programming for instance — anything that divides a problem into well-orchestrated parts. But obviously that level of modularity is not desirable in a novel. And yet there had to be something, right? It doesn't just happen by accident, that's for sure."

Like a coder, Wroblewski set to work trying to understand the elements of narrative structure from experienced writers at school, and endlessly hacked his manuscript. "You develop a lot of habits when you write software that are helpful in writing novels," he says. "One of them is simply holding in your mind a very large, complicated structure of some kind. A complex set of moving parts." Likewise, he usability-tested his manuscript, debugging it by talking "some poor slob into reading it and telling me which parts worked and which didn't." Over a decade, he wrote eight drafts. Only then was it good enough, in his mind, to show an agent.

The book was published June 10, and got a great review in the Times four days later. The following week it hit the best-seller list. This should please him, but Wroblewski is still a software dude. "What bothers me is there's not 2.0 process," he says. "I can't go back and release a new version." Then again, he doesn't have to worry about Google stealing his business.