Prison art from Muslim detainees in the London show Captivated: Art of the Interned.

As London shows go, most of the art is pretty poor: a few pots, a couple of paintings, some cartoons and doodles, displayed in the back room of a charity in a commercial street. But Captivated: The Art of the Interned is a quietly damning indictment of Britain's treatment of post 9/11 terror suspects. Opened the week after Gordon Brown's government won the right to extend detention without charges to 42 days, the exhibit is a glimpse of the thoughts and longings of interned terror suspects.

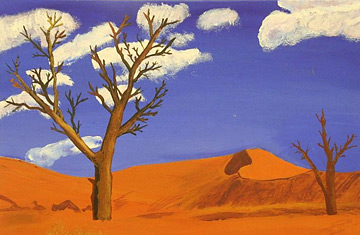

They are reassuringly banal. There are paintings of sand-dunes, palm-dotted horizons, tranquil seas; 'Detainee Z,' an Algerian engineering student detained without charges, then released on bail under supervision, after London's July 7 bombings, built a cherry-red wooden toy train for his son. A boat called the Allahu Akbar, its sail adorned with cut-out photos of Mecca and Jerusalem's Al-Aqsa mosque, is made out of matchsticks. So too is a model of an Andalusian Mosque, complete with arches and pillars, and a jewelry box embossed with 'Najat,' the name of some prisoner's beloved. "It actually makes me quite proud that these men that are so demonized are capable of producing these pieces of artwork," says Moazzam Begg, a British man who was an inmate at Guantanamo until he was released in 2005. He conceived of the show after seeing a museum displaying artworks by prisoners held during Ireland's Troubles, and worked with the human rights group Cage Prisoners to sponsor the show. "When one sees what a father makes for a son, what a husband makes for his wife, it humanizes them."

Captivated opened the same week that Human Rights Watch issued a report on Guantanamo prisoners, noting that prolonged isolation had led to declining mental health. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other illnesses loom large in many of the artists' detention biographies. Perhaps the most skilled piece of work, a graceful glazed vase decorated with delicate yellow flowers and bold geometric shapes, is the work of 'Detainee B,' an Algerian who sought asylum in the U.K. only to be arrested in 2002 without charges or trial. Held in London's Belmarsh prison in solitary confinement for 22 hours a day, he was a support for other Belmarsh inmates with mental health problems. When art classes were stopped due to security concerns, his own mental health declined, and he was transferred to a prison for the criminally insane. He was later released, but has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals ever since and remains in one today.

Like many of the interned, 'Detainee B' also wrote poetry. His My Friend, the Highlandress, a tribute to a Scottish campaigner for terror suspects, contains one of the few slivers of levity in the show: in gratitude, the North African Muslim offers to wear a kilt of her clan, the MacDonalds. The other poems posted on the walls are darker. "Have you visited the graves of the living?/In Belmarsh there are two such blocks," writes Adel Abdel Bary, an Egyptian lawyer arrested after the 1998 bombings in East Africa.

Begg wrote poems in Guantanamo, several of which were included in the collection Poems from Guantanamo, published last fall. But for Guantanamo detainees, for whom "getting a pen required an Act of Congress," he says, paint and clay were out of the question. "When I see what these [British detainees] were allowed, I think, 'Fantastic, I'd love to be in a prison where people could make these things," says Begg, who recalls fellow inmates fashioning tiny sculptures of spiders and scorpions out of toilet paper doused in cold tea. All were taken and thown away, says Begg, as potential security risks. Guantanamo's poets, not allowed pen or paper in their first years of detention, wrote short poems on Styrofoam cups from meals, which they passed from cell to cell.

The London show's most moving exhibits are those that hide their creators' desperation. The pretty jewelry boxes built for wives, and Adel Abdel Bary's cards for his daughter, Rahma, decked with bright hearts, flowers, and "I Love You's" aren't art. But seen as a whole, the show Captivated is as eloquent about the grey, ghostly nature of 21st century warfare as any true artist could hope to be. The show, at 12 Old Street in London, runs until July 4.