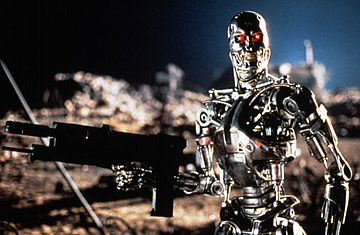

A scene from Terminator 2, for which special effects artist Stan Winston won two Oscars, for Best Makeup Effects and Best Visual Effects

A T. Rex roars into view in Jurassic Park. An army of Schwarzeneggerian cyborgs clang after Linda Hamilton in The Terminator. The mommy monster of Aliens slavers at Sigourney Weaver. The Predator—a gigantic, dreadlocked Creature from the Black Lagoon—stomps through a South American jungle.

When a child screams in delicious fright as these image leap from the screen and into the brain's trauma center, any parent will whisper a consoling "They're not real, honey." They are, though—as real as any nightmares the dream machine can conjure. But a machine didn't dream up, design, build, or give festering life to these creatures. Stan Winston did.

Winston, who died Sunday at 62, after a seven-year bout with multiple myeloma, probably gave more kids more sleepless nights than anyone in Hollywood. Yet he wasn't out simply to scare the audience; he wanted to create complex, often sympathetic figures— to enlighten us about the dark side. "I don't do special effects," he once said. "I do characters." His Edward Scissorhands character, elaborated on from director Tim Burton's sketches, puts the poignancy right in that white, sweet, baleful, soulful face. The Penguin, played by Danny De Vito in Burton's Batman Returns, is an ugly, beaky thing that no kid could mistake for having happy feet; yet beneath his comic rage there's an abandoned child's ache, palpable and, thanks to Winston, visible.

In remarks about his vocation, Winston always emphasized the artistic impulse over the tinkerer's gift. "I am not a technician," he said. "I am techno-ignorant." (Here, he must have been kidding to make a point, since he was in charge of the Stan Winston Studio, which constructed these elaborate, often revolutionary mechanisms in addition to devising them.) "But I love creating characters and telling wonderful stories." Another hint to Winston's humanity: his insistence on paying at least as much attention to his family as to his job. He leaves behind his wife Karen, their two children and four grandchildren.

HOW TO MAKE A MONSTER

Stan Winston was of that small, brilliant, edifyingly demented breed of special-effects makeup men. Not visual effects, you understand: these folks don't sit at computers and play with pixels, a technique that requires an actor to stand in front of a green screen and mime fear. They are old-fashioned craftsmen, using spirit gum and other medieval (and modern) applications to devise prostheses so horrid, so hand-made, they'd scare anyone on the set. In a tradition stretching back to silent-film star Lon Chaney, the SPFX makeup men, in essence, build scary masks. They make horror visible by sculpting it.

Before Winston, there were two masters of horror makeup who names are so ordinary, they could be scrawled in a motel register by a teen seeking furtive sex: Jack Pierce and Dick Smith. Pierce, during his time at Universal Pictures in the 30s and 40s, created the studio's entire monster menagerie: Boris Karloff's Frankenstein and the Mummy, Bela Lugosi's Dracula, Lon Chaney Jr.'s Wolf Man, Claude Rains' Phantom of the Opera.

Smith, whose career spanned a vigorous half-century and who's still around at 86, gave Dustin Hoffman his simian, centenarian face in Little Big Man, puffed Brando's cheeks in The Godfatherand turned 13-year-old Linda Blair into a puking, head-swiveling demon in The Exorcist. Imagine any of these films without Pierce's or Smith's contributions, and your mindscreen plays a much more ordinary movie. No sleepless night for the kids, either.

Winston's most notable contemporary has been Rick Baker. Born in 1950, he rose to prominence with director John Landis, lending his antic artistry to that lycanthropic masterpiece An American Werewolf in London, to Michael Jackson's moonwalking zombie in the Thriller video and to just about any movie where Eddie Murphy looks like someone else: a Caucasian alterkocker in Coming to America, a morbidly obese mama in Norbit and, of course, all of the Klumps.

Baker is the one FX makeup artist to snag more Oscars than Winston did: six, to his four. But he's had competition from his one-time apprentice Rob Bottin, who designed John Carpenter's threatening Thing, the original RoboCop and the twisted uggies in Total Recall. And a tip of the skull to Tom Savini, "the Godfather of Gore" who's made every known body part, and a few that should have remained unknown, drip, crack or explode in his six fright films with George A. Romero.

FROM GARGOYLES TO IRON MEN

Botttin and Savini had FX makeup in their blood from childhood. They were of the generation inspired by the trail-blazing work of Winston and his tiny band of predecessors. Winston came to Hollywood in 1968, long before the lovingly detailed rendering of the grotesque had become fashionable. Back then, most films were photographs of people talking, and action movies were photographs of people fighting. Young Stan arrived in town hoping for work as an actor. With no jobs coming, he joined the Makeup department at Disney. The studio had its live-action and animated films, but it had also pioneered audio-animatronics in its theme parks and at the 1964-65 New York World's Fair. It might seem a long leap from the international singing dolls of "It's a Small World" t0 the troop of steely Terminators, but the physics are the same.

By 1974 he had won two Emmys: for the gremlin-like creatures in the TV movie Gargoyles and (shared with Baker) for the old-age makeup worn by Cicely Tyson in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. Moving into feature films, he forged productive relationships with directors as imaginative as he: Burton, Steven Spielberg for Jurassic Park and A.I. and James Cameron on Aliens and The Terminator, T2 and the Universal Studios park attraction, T2: 3D, an amazing blend of film, FX and live action that Winston co-directed.

Sometimes he built on the design work of others. He adapted H.R. Giger's creature from Alien for the mommy monster in the sequel, and developed Bottin's FX of the wormy, slightly Strom Thurmonish invader in The Thing. (Note to the budding creators of creatures: When in doubt, give them an extra set of teeth—the better to eat you with, my dear.) Winston's ickiest godchildren would face off in Alien vs. Predator and a 2007 sequel, which he sat out. That stuff was mostly computer-generated, anyway.

By the time of Jurassic Park, in 1993, the seven-ton T. Rex he built was only part of the visual trickery. The rest was the breakthrough digital sorcery supplied by George Lucas' Industrial Light & Magic. Since then, fans have wondered apprehensively, is Winston's an obsolescent art? (In his last days he was transforming his studio to emphasize the digital.) Will makeup effects soon seem as anachronistic as the papier-mache monster suits worn in the grade-Z horror movies off the 50s?

No, as long as directors find symbiotic inspiration in minds as fertile as Winston's. (At his death he was working on Cameron's Avatar.) His finest achievements in his last decade, as he tried battling cancer to a draw, were the robot Teddy in A.I.—another melancholy mandroid in the Scissorhands style—and, just this year, the suit that Robert Downey Jr.'s Tony Stark fashions in Iron Man. Stark's basement laboratory might have been Winston's workshop; the dedication and ingenuity Stark lavished on his jet-propelled armor were worthy of Stan the Man himself.

On the digg.com website this afternoon, as news of Winston's early death spread through the blogosphere, two fans bade him farewell in a way the creator of the Terminator would have appreciated. "Hasta La Vista," wrote one. Another added, "He'll be back."