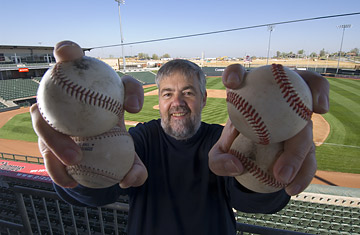

Portrait of baseball statistician Bill James holding 4 baseballs at a minor league field near his home in Lawrence, Kansas.

Bill James, the legendary baseball stat guru and godfather of the data-driven "Moneyball" movement that has changed how front offices evaluate players, has written a new book, The Bill James Gold Mine 2008. TIME's Sean Gregory caught up with James, now a senior advisor to the world champion Boston Red Sox, from the team's spring training facility in Fort Myers, Fla., to talk about the state of analytics in baseball, the Roger Clemens steroids controversy, and whether a certain New York Yankees star looks like Henry Fonda.

TIME: This new book is a collection of essays, with statistical nuggets sprinkled throughout. How'd it come about?

James: I've been looking, for a long time, for way to have a casual interaction with my audience. And so I started an online service where I talk to my audience, kind of every day. And, in the process of doing that, we developed a lot of charts and profiles that are useful for online, and I've written a lot of articles that are posted online. And the book is a summary of some of the most interesting stuff from online.

What nugget surprised you the most?

Brad Hawpe of the Colorado Rockies had just a fantastic year getting clutch hits. In my view, he was clearly the best player getting clutch hits last year, driving in about 45 runs in clutch situations, not counting the post-season. That was by far the most in the majors. A lot of regulars, all season, don't drive in 10 runs in the clutch. Driving in 45 runs in clutch situations is a huge thing. So that was probably the biggest surprise to me, because I had no idea that that was true.

For the book you developed a mathematic measure of consistency in a ballplayer. Who is the most consistent player of all-time?

It's not a surprise. The most consistent player of all-time is Henry Aaron. He had the same numbers every year that he had the year before. In our own generation, Albert Pujols has been as consistent as Aaron was. In fact, he's been more consistent. But backing away from it and looking at the whole career, the number one guy would have to be Aaron.

After poring over all the data, what player was much more inconsistent than you would have previously thought?

There are a lot of players that go up and down. But it would be hard to top Henry Aaron's teammate for 10 years, Rico Carty. Rico Carty went from being the best player in the league one year, to being injured or useless the next year. It was pretty much a regular thing for a long period of time. As a model of inconsistency, he was it. [More recently, ex-New York Yankee third baseman Scott Brosius, MVP of the 1998 World Series, gets a miserable "D+" consistency grade from James. Ex-outfielder Eric Davis, a two-time All-Star and solid player throughout his 17 seasons from 1984-2001, gets just a C]

My favorite parts of the book were the "stupid" awards that you gave out. And I'm quoting stupid because you called them stupid.

I call them stupid cause they are. That's basically it.

My favorite is the Dave Kingman award, which is given to the player who, through the formula you created, is shown to "best exemplify the idea of hitting home runs without doing anything else positive as a hitter." It was my favorite award despite the fact I was a huge Dave Kingman fan growing up. He was a famously prickly guy — has he sent you any angry letters or anything for naming this award in his honor. Or more like his dishonor?

I doubt he's heard about it yet, the book just hit the stands. I look forward to perhaps getting a nicely wrapped dead gerbil or something like that [in the 1980s, Kingman infamously mailed a dead rat to a reporter. Past winners of this "award," besides Kingman, include Steve Balboni, Fred Lynn, Sammy Sosa, and Mark McGwire. The 2007 winner was Cincinnati Reds catcher Dave Ross, who hit 17 home runs — with a mere 39 RBIs. He hit just .203, and struck out 92 times in 311 at bats.]

You use some colorful language in the book, making the reams of statistical information much more reader-friendly. At one point, you basically compare teams that use the shift against Boston Red Sox star David Ortiz to "Polocks hunting landmines." You say they're "dumb." Though you are quick to point out that there are only "three Polish guys" who are "offended by Polock jokes." Why push the envelope?

Everybody who is my age, or everybody who is over 30, knows that joke. I mean, I'm not sure I get the point of the over-shift against David Ortiz. It helps you if he hits a ground ball, but if the bomb goes off, you can put those infielders anywhere you want to, it doesn't really do you any good. The damage that David does comes when he hits the ball 380 feet. It really does not matter much where you put your infielders when that happens.

This brings up an interesting dilemma. You work for the Boston Red Sox, yet you're basically telling teams they're not gaining any advantage shifting on David Ortiz. Are you conflicted? Did you ever think, "I don't want to tell people that information, I work for the Red Sox, I want them to win?"

Yeah, I have to engage in a balancing act as to what I can say, and what I cannot say, pretty much all the time. I did weigh it. 'Is this something I should say? Is this something I shouldn't say?' People are good enough to credit me with a lot of influence, but I think the next time some team reads one of my books and thinks 'Okay, we'll stop shifting on David Ortiz,' will be the first time that something like that has happened. I try to be careful. There are some things I can't say. But on the other hand, you're writing a book. Your responsibility is to the reader, not to the Red Sox.

Did you have to clear the Ortiz section with the Red Sox?

That particular nugget? No. I tried to make sure the Red Sox knew what I was doing, because I didn't want to blindside them. But I didn't exactly clear anything. I used my own judgment.

You often show that conventional baseball statistics aren't as important as they appear. In the book, you write "every year that passes, the ERA (Earned Run Average) becomes a little more irrelevant." Why is that?

The reason the ERA is becoming a little more irrelevant every year is that pitchers don't pitch whole innings anymore. Relief pitchers anyway. If you go back to 1915, 1920, really, all pitchers pitched full innings 99% of the time. And you could measure a pitcher's effectiveness by how many runs he allowed in those whole innings. But modern pitchers, in particular modern relievers, pitch portions of an inning. And in a situation where each pitcher pitches a portion of an inning, who you charge the run to becomes critical. And the rule on whom we charge the run to is so careless and sloppy that it doesn't work. It often leads to pitchers having ERAs that do not reflect how they really pitch, either because the reliever allowed a bunch of runs to score that were charged to somebody else, or because the starting pitcher who left guys on base got hurt by it.

What do you think is the most useless statistic in baseball today?

Wow. There are so many candidates. You get really useless stats when you break them down into very small at-bats. So the stuff that appears on centerfield scoreboards during ballgames, a very high percentage of it tends to be totally useless. It's of the nature of — and I'm not trying to parody it — it's of the nature of, "John Robinson hit .396 after the sixth inning this year." You know, as if he had an ability to hit after the sixth inning. It's virtually impossible to explain how such a thing happens. Looking at the data, you would just say, "it's a data glitch, so what?" That sort of small sample data glitch tends to dominate television broadcasts sometimes, and very often the fan information sections at the ballpark.