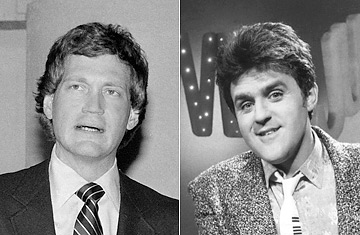

Comedians David Letterman and Jay Leno

(2 of 5)

A labor movement was born. Tom Dreesen, who had been in the Teamsters Union when he worked on the loading docks in Chicago, became the comedians' chief organizer and spokesman. A former G.I. who was a few years older than most of the youngsters at the Comedy Store, Dreesen had little affection for the college kids who had protested the Vietnam War, but he provided an articulate voice for their working stiffs' complaints. He tried to appeal to Mitzi's sense of fair play. "I told Mitzi, you pay the waiters, you pay the waitresses, you pay the guy who cleans the toilets. Why don't you at least pay the comedians?" Many of the struggling kids who were helping her clubs thrive, he argued, couldn't even afford to buy groceries. On New Year's Eve he had run into one of them, on a high after finishing a set at the Westwood Comedy Store. "He said, it was fantastic, I killed 'em, had the best show I ever had. And then he said, 'Tom, can you loan me five dollars for breakfast?' I told Mitzi that story and she said, 'Well, he should get a goddamn job.' I said, 'Mitzi, he has a job. He worked for you on New Year's Eve.' "

The comics formed a quasi-union, the Comedians for Compensation, and held meetings. The first one was mass chaos, says Dreesen, "Everybody's talking at the same time. Gallagher's yelling, 'Why don't we burn the fucking place down!' It was insanity." David Letterman was there, along with his good friend George Miller, who was particularly outraged because his mother used to work as a bookkeeper for Mitzi Shore — and thus knew how much money she was socking away. Leno came too, though Letterman thought he made something of a spectacle of himself. "Jay, bless his heart, couldn't sit still," he says. "He was behaving like a hyperactive child. Jumping up and down, being funny and distracting, to the point where everybody sort of thought, well, maybe we shouldn't tell Jay about the next meeting." Dreesen eventually took over the meetings, running them according to the Robert's Rules of Order he had learned when he used to chair meetings of the Jaycees.

Mitzi was willing to relent on the comedians' most reasonable demand, the one that had sparked the whole uprising, agreeing to pay the comics who performed in the Main Room one half of the cover charges. But while that was fine for the top tier of comics big enough to play the Main Room, it meant the vast majority of lesser names would still be working for nothing in the Original Room. So the comics turned it down and dug in for a fight.

Dreesen went back to Mitzi and tried to negotiate a plan for paying all the comics, not just the Main Room elite. He suggested what he thought would be a painless solution: simply add $1 to the $4.50 cover Mitzi was charging at the time, and split that extra dollar among the comedians. If a couple hundred people were in the club on a given night, that meant $200 split among the comics; it wasn't much, but it was a start, and even those few bucks could mean a lot. But Mitzi turned him down flat. "She said no, they don't deserve to be paid," Dreesen recalls. "I knew then that we were in trouble. I thought it was about money. It was about control."

In late March of 1979, with the talks at an impasse, the comedians went on strike. A picket line was assembled in front of the Comedy Store on Sunset Boulevard, the strikers carrying placards with slogans like no money, no funny and the yuk stops here. The spectacle of stand-up comedians, many of them well known from television, recasting themselves as extras in F.I.S.T., was an irresistible national story. Johnny Carson made jokes about it on The Tonight Show. Some of the more established comics were scornful ("This strike is the biggest joke I've ever heard come out of the Comedy Store," quipped David Brenner). But among the younger comedians it was a serious matter, and the vast majority of the 150 or so who worked at the Comedy Store walked off the job. Some of them had careers outside the club and didn't need the money, but supported the strike nevertheless. In the midst of the walkout, Letterman filled in for Johnny Carson as guest host of The Tonight Show. Immediately after finishing the show he drove to the Comedy Store and joined the picket line. "This was the umbilical cord for a lot of guys, myself included," says Letterman. "Money wasn't necessarily an issue for me, because I had a couple of bucks in the bank. But for these other guys, this was it. This was sustenance." Richard Lewis, who had moved on to concerts and television, wouldn't join the picket line but thought the cause was just. "I didn't want to picket, because I didn't want to say to the owners of the clubs, 'I need your twenty bucks.' To me, it trivialized my goal," says Lewis. "But once I saw the bigger picture, that people were making no money, I said, this is bullshit. I was totally pro-strike."