The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

Death may be, as the cliché has it, the ghost haunting the attic of everyone's mind, but the movies don't usually play it that way. They turn it into melodrama's force majeure, the sneering, swaggering (and generally well-armed) bully it is the hero's duty to resist and ultimately defeat — thoughts of his own inevitable mortality being matters for that last reel that no one ever bothers to shoot. Or think about.

Mostly, we wouldn't have it any other way. Which does not, perhaps, bode particularly well for The Diving Bell and the Butterfly or The Savages, both of which take mortality seriously. In the former a successful man in his prime is struck down by a massive stroke. It leaves him able only to blink a single eye. And the capacity to conduct interior monologues with himself. In the latter, a cranky old crock named Lenny (Philip Bosco) surrenders to senile dementia, leaving his self-absorbed and obscurely damaged children, Wendy and Jon (Laura Linney and Philip Seymour Hoffman), to devise a minimally dignified exit strategy for him.

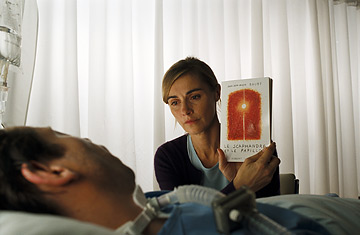

To say that Julian Schnabel's film about the catastrophe that struck Jean-Dominique Bauby (Mathieu Amalric) , editor of a chic Paris magazine and a glamorous figure in France's celebrity world, is a exercise in minimalism rather understates the case. Visually speaking it consists of Jean-Do (as he prefers to be called) lying in bed, observing his radically limited world and recalling his life. What it has for a plot is Jean-Do devising a way to write a book. A therapist recites the alphabet to him, and whenever she mentions the right letter to him, he blinks his eye once (two blinks indicate a negative). Thus does he create, letter by painful letter, the best-selling volume of which this movie, written by Ronald Harwood, is the adaptation.

Any book represents a challenge to mortality, an attempt to take something of oneself and give it a life outside one's foredoomed body, and this is, perhaps, the most heroic such effort ever made. As a writer, I admire it greatly. Without wanting to sound like a pompous twit, I think it's the only worthwhile reason to do what we do. As a moviegoer I'm less certain about the movie's effectiveness. Schnabel has an alert, imaginative and unsentimental cinematic eye. He does everything he can to involve us in Jean-Do's struggle against stasis, which is perhaps less a "triumph of the human spirit," a fatuous phrase that ought to be banned from critical discourse, than it is a triumph of the human ego. This is all right with me — I don't think anything worthwhile is created without egotism pushing the effort along and it is good to see it functioning in such extreme circumstances. But still, somewhat shame-faced I have to admit that at some point in the film I began to hear a subversive voice whispering in my ear, and what it was saying was, "Could you blink a little faster, pal?"

You don't have to be a writer to feel for the Savage family in their distress. If you're an aging human being you have to have thought grimly about the almost inevitable exigencies of the endgame that you're probably about to endure. If you're the child of senior in danger of losing his citizenship in the rational world, you have to have thought about how to handle a parent's endgame. In writer-director Tamara Jenkins's intricately wrought movie, the old guy's children are flirting with middle age without much to show for it. Wendy is an unproduced playwright prone to bad fantasies (health) and good ones (she imagines she's won a Guggenheim fellowship). She's having an affair with a remarkably agreeable married man (the excellent Peter Friedman) that's not going anywhere, and she has an obscure desire to make up for past hostilities by placing her old man in a fancy nursing home. As her brother Jon points out, the patient really won't be able to discern the difference between that and more affordable accommodations. Jon, however, is a somewhat withdrawn, phlegmatic and therefore somewhat unpersuasive man. A slightly shabby scholar in dismal Buffalo, he's writing a book on Brecht, while doing his best to avoid what seems to be a promising relationship or, for that matter, any adult responsibilities. He's a grad student in perpetuity.

The younger Savages are, in short believably ordinary, mildly damaged people, and nothing very dramatic happens as they cope with their rather ordinary problem. Yet Jenkins makes us feel the false cheerfulness and emotional emptiness of nursing home life. Better still, she rather subtly shows how Jon and Wendy's enforced concern for someone they don't really like very much forces them out of their defensive crouches — forces them, too, to take somewhat better control of their own lives. I wouldn't call the film inspirational — it is too well observed to succumb to easy sentiment — but its realism is patiently engaging and subtly insinuating. And Linney and Hoffman are extraordinary; refusing to beg for our sympathy, they earn it moment by quotidian moment in performances so good, so lacking in showy effect, that they are almost certain to be overlooked this awards season. But that's OK. Honesty tends to receive its own, more lasting rewards in our remembering hearts.