Forty-five years later, I live in New York but I'm still a night person. I have my transistor radio on and idly attend the current Milkman's Matinees: the NPR crew for judicious patter, choleric Joe Benigno for the latest geshrei about his pathetic Mets, Art Bell for early warnings on Y3K. And lately I've been wondering, Where's the damn poetry? I want to hear that Midwestern voice in the night, soothing and urgent, as personal as a confession whispered in the back booth of a bar just before closing. I want to hear him read some scary fiction or corny old poetry, play his nose flute, then get us all to open our windows and shout, "Excelsior, you fatheads!" Most of all, I want to hear the rest of the story about this kid, see, the young Jean Shepherd, full of himself as he goes out with this girl, until he realizes — in a thunderclap of understanding and horror, and at the climax of a 45-min. monologue that is perfectly timed to end at the top of the hour — "I was the blind date!"

|

The show must have entranced a lot of East Coast kids in the wee smalls, to judge from the dozens of tributes on some Shepherd websites. Almost all of them begin: I was a kid with my transistor radio under the pillow, and there was nothing brighter or more comradely than being alone with Shep in the middle of the night. In the excellent two-hour radio retrospective "Jean Shepherd: A Voice in the Night," which airs occasionally on NPR stations, Paul Krassner was 25 in the late '50s, but he too was warmed by Shepherd: "My idea of a hot date would be to find a girl who also liked Shepherd and lie in bed with her all night listening to Shepherd." I wonder if Krassner, who as editor of The Realist later printed some of Shepherd's pieces, ever told him that he was Krassner's equivalent to a Sinatra album: an aural aphrodisiac.

At the start, Shepherd had been a long shot for even cult status with smart East Coast big-city kids. He had spent more time in the Army (Signal Corps during World War II) than in college; he was older than he seemed (or said); he had been married and divorced after fathering two children whom he would ignore for the rest of his life. He had worked in radio and TV for a decade, in Cincinnati and Philadelphia, before he got to New York. Steve Allen, an early admirer, had recommend Shepherd as the first host of "The Tonight Show" (Allen himself got the job), but his career wasn't skyrocketing. The all-night slot at WOR was no plum; before he came, the time had been filled with elevator music. He didn't even work in the station's Times Square studio; he had to do his show from the transmitter. It's as if he was hired to be exiled.

Shepherd's style didn't seem a good fit for New York. He was as skeptical of liberals as of conservatives. His voice, for all the drama in its tone, was stoutly Midwestern. And so was his favorite topic of discussion: he located most of his stories in the small-town Indiana of the '20s and '30s. Shepherd was a strange species: the hip hick, a defender of the Midwest at the precise moment that America was becoming bicoastal. He wasn't funny, in the recognizable joke- telling way; he was a humorist, which someone once defined as a standup comic who's a nice fellow but doesn't make you laugh.

All right, a certain stripe of intelligent, lonely, pimply teenager thought he was great. But that was soooo long ago; kids love to have anyone talk to them in secret; and how qualified are they to judge the art of the monologue? Why should anyone today care about a radio chat-person? Anyway, radio programs just go into the ether.

As it happens, quite a few of Shepherd's shows didn't disappear. They are available, both for purchase and listening; Max Schmid, a night jock on New York's WBAI, sells the tapes, has some on his website and generously, not to say perversely, plays 45 mins. of Shepherd every Tuesday-at 5:15 A.M.! So once a week I would set my alarm and again wake up, in what for me is the middle of the night, to hear Jean Shepherd. Age has not withered his wit, nor death stayed the variety of subjects he summons and moods he evokes. It nice for old Shepherd fans to have archaeological validation that, when they were young, dammit, they were right.

THE TALK

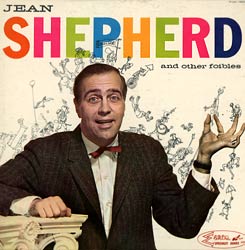

Jean Shepherd had a full and varied career. He wrote four books, most of them

collections of short stories published in Playboy, which also chose him as the

man to ask the questions when the Beatles sat for their Feb. 1965 Playboy

Interview. Shepherd improvised the narration for the title cut on Charles

Mingus' 1958 album "The Clown." He scripted four hour-long comedy-dramas for

PBS's "American Playhouse." He may be the only journalist to have contributed to

Mad and Mademoiselle, Reader's Digest and The Realist, Audio Magazine and TV

Guide, Field & Stream and Town and Country. He performed on Broadway and,

Saturday nights for three years, at the Limelight in Greenwich Village. He was

the voice on Volkswagen commercials and, for a week, the co-host of "Today." He

helped write the script, based on his monologue and short story, for that not-

quite-deserving holiday perennial, "A Christmas Story." He died on October 16,

1999.

Basically, though, he had the same job description as thousands of men before and after him: he was a guy who talked on the radio. But nobody talked as seductively as he did, or as much, for more than 40 years, most of them on WOR. On that late-night shift (which lasted only eight months), then for four hours Sunday nights and in a nightly slot through the '60s, Shepherd pretty much invented talk radio. Real talk, conversation, where the listener has to be as receptive as the speaker is creative. Shep certainly invented "free-form" radio; without him, the whole Pacifica network might have had no format. The Shepherd style fragmented and spread through the radio cosmos. Garrison Keillor got a big chunk of it, Jonathan Schwartz a little; the alternative-music jocks got some. Harry Shearer (producer and narrator of "A Voice in the Night") nourished it on the West Coast. Much of the rest devolved into Rush Limbaugh and his less mesmerizing clones.