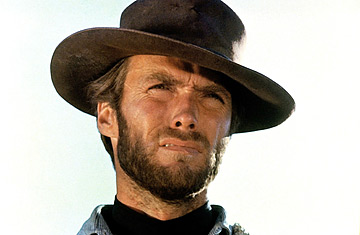

Clint Eastwood in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

(2 of 2)

On TV and in the movies, the work of the Western was to reconcile the individual and civilization, the man with the gun and the pretty school teacher. For the hero to be the best shot was also to say that the little people in the community were safe as long as it had a strong, armed protector — a one-man army, a preternatural policeman, the Old Testament God — on their side.

The spaghetti western changed that. Sergio Leone filched the plot from Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo (Hollywood had already remade Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai as The Magnificent Seven) for his 1964 Fistful of Dollars. Clint ambles into a rotten town commandeered by rival miscreants and takes both gangs down. In Fistful and the Leone-Eastwood followups For a Few Dollars More (surely the most honest title every slapped on a sequel) and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, society was run by outlaws. The moral choice was among various shades of black. Anarchy ran riot, and the only recourse was martial — not marshall — law.

But the audience needed a rooting interest, and because Clint was so damn cool, he established the new mode: hero by default. The good guy was the one with the fastest gun, the meanest scowl and top billing. And that perpetual three-day beard that Toshiro Mifune had worn in the same role in Yojimbo; in Hollywood Westerns, the hero's visage was typically hairless, while villains sported a dastardly mustache. Eastwood's scruff became a fashion statement that lives today on the carefully unshaven faces of pop stars and young actors. And his surliness, transposed to the Dirty Harry Callahan character he played in five films, lent the cop film an antiheroic attitude the genre still can't shake.

Hollywood, when it brought Fistful to the States, still wanted moviegoers to think the Italian Westerns were American, though Eastwood was the only Yank on the set. So Clint's costar, Gian Maria Volonte, is called Johnny Wels on the U.S. credits; composer Ennio Morricone is Dan Savio, cinematographer Massimo Dallamano is Jack Dalmas. In some versions, Leone was called Bob Robertson. The American edition bore no screenplay credit, and of course no reference to the original literary source.

But audiences didn't care where it came from; they loved it. Produced for a thrifty $200,000, of which Clint got $15,000, Fistful made the careers of Eastwood, Leone and Morricone. It created a legend around the Man With No Name — a publicist's canny invention, since the Eastwood character always had one (Joe, Mongo, Blondie). And it triggered literally hundreds of Westerns from an Italian movie industry that had already shown itself expert at imitating Hollywood and British genres: the Biblical epic turned into the sword-and-sandal muscleman movies, the sex-charged Hammer and Corman-Poe horror films made into even more erotic thrillers. For ordinary moviegoers of the 60s, the phrase "Italian films" did not conjure up Fellini, Antonioni and the glamour of alienation. It meant vigorous ripoffs of English-language genre films.

Among the prime directors of Italian Westerns (most of them shot in Spain, by the way) was Sergio Corbucci, who vaulted to prominence with the 1966 Django. It was The image of star Franco Nero coming into town not on horseback but on foot, dragging a coffin, was an instant sensation that cued more than 50 Django films, all unrelated to the original. Its theme song, by composer Luis Bacalov, remains one of those melodies that worms its way into a listener's brain and, as I can testify, can't be extracted for weeks. The Corbucci film also inspired later generations of video hounds, including Quentin Tarantino, who appropriated the Django scene of banditos cutting off a preacher's ear for his film Reservoir Dogs. (The original went further: the poor man had to eat his ear.)

Corbucci went from hot to frigid with The Great Silence (1968), a snowbound Western in which a mute Jean-Louis Trintignant, the Man With No Voice, sets out to even the odds against the nasties who cut out his tongue. It's a plot similar to the film Leone was making that year: Once Upon a Time in the West, another decades-old revenge story and one of the great, elegiac Westerns. It was horse opera rendered as grand opera, with Morricone's fullest, most voluptuous score. Corbucci's vision was much bleaker. For once the good guy doesn't win. Hero and heroine are both killed, and the rival bad guys are left to shoot it out in a final saloon carnage.

For all its influence in Europe and Asia, Django got no Stateside release that I know about. In fact, few spaghetti Westerns beyond the Leones were released here. Americans stuck with the Duke through True Grit and patronized the anti-Westerns of Sam Peckinpah (notably The Wild Bunch) and Robert Altman (McCabe & Mrs. Miller, another snowy oater). And then, bang, the genre was dead. The setting, the pace, the moral stakes all seemed so very 19th century. When the Western is periodically revived, it's not from popular demand but from the antique obsessions of powerful filmmakers.

And they're often as remote from our shores as the Italians. The stars of the new 3:10 to Yuma are the Australian Russell Crow and the Brit Christian Bale. The writer-director of The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is the New Zealand-born Andrew Dominick. Today, as in the 60s, the Western holds more fascination for outsiders than for Americans. But if the genre is to rise from the dead one more time, the grandsons of the pioneers — the descendants of those millions of viewers who made the Western a unique contribution to popular art and culture — will have to saddle up and see a few.