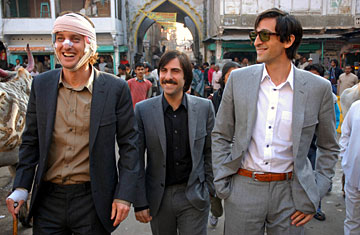

Left to Right: Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman and Adrien Brody in Wes Anderson's The Darjeeling Limited

He looks a mess — funny, in the context of the film; not so, given Wilson's hospitalization a week ago for what was described as a slashed-wrist suicide attempt. The actor was released Saturday and is in his Santa Monica home, People.com reported, under 24-hour watch by friends and family, instead of on the red carpet in Venice.

In the movie, Francis is a man on a quest: to reconnect with his brothers Peter (Adrien Brody) and Jack (Jason Schwartzman). They've met in India, on a long train trip, for what Francis hopes will be a three-way spiritual quest. "I want us to be completely open," he tells Peter and Jack, "and say yes to everything, even if it's shocking and painful." OK, then, Peter has an open question for Francis: "What happened to your face?"

He had an accident, Francis replies, and banged himself up pretty severely. Of his surgeons, he says, "They did all the procedures right, the result of which is I'm still alive." He admits he has "some healing to do," to which Jack cheerleadingly says, "Gettin' there, though," and Peter offers the compliment, "Gives you character." Later Francis reveals that the incident was not quite an accident: "I smashed into a hill on purpose on my motorcycle."

This — along with the fact than Wilson is one of three brothers (Andrew and Luke are in movies too) — concludes the witness report on the coincidences between Francis Whitman and Owen Wilson. Enough already. I feel creepy just passing this information along, as if a critic were auditioning to be a coroner.

Yet, sad as the news is about Wilson's medical condition, what registers most strongly in Darjeeling is his sweet deadpan charm. What's amusing about all his bandages, which make his head as turbaned as that of the Sikh fellow who runs the train the brothers are on, is now how he wears them but how he ignores them; it's as if Francis is having a bad hair day everyone notices but him. Speaking in an intense whisper, Wilson unleashes all kinds of crackpot or domineering suggestions that somehow make momentary sense. He's what actors have to be: salesmen of dreams, carriers of seductive toxins. Wilson always makes the improbable plausible.

But I fear Darjeeling, which opens the New York Film Festival Sept. 28 and will play in major cities shortly thereafter, is beyond even Wilson's powers of persuasion. It's basically the story of three well-heeled guys on one of those self-help vacations that upper-class searchers took in the '60s. Go to India and get your life validated by the Maharishi. Or get good drugs at fire-sale prices. This could have ended up as a Midnight Express nightmare, except that the Whitman boys' luck is a little better, a little weirder. One of them finds romance with a train hostess (lovely Amara Karan). Two of them save local children from drowning. They meet up with their mother (Anjelica Huston) — the source, we soon realize, of some of the boys' bad habits.

Picaresque movies often feel longer than they are. For them to work, they need an interior spring with more thrust than Darjeeling's attempt at reconstituted brotherhood. The problem is in Anderson's approach, which is so super-cool, it's chilly. In his elaborate visual construct, virtually every shot is followed by with the camera point-of-view shifted 90 or 180 degrees — which is geometrically groovy, no question, but pretty quickly predictable. Same goes for his stories, which rely on gifted people behaving goofily. Anderson has the attitude for comedy, but not the aptitude. His films are museum artifacts of what someone thought could be funny. They're airless. Movies under glass.

Wilson has appeared in all five of Anderson's feature films (Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and the new one) and co-wrote the first three — the ones I prefer in the the director's oeuvre. The script here is by Anderson, Schwartzman and Roman Coppola (Francis' son, Sofia's brother) and it doesn't add luster to anyone's reputation.

The Darjeeling program includes a related 13-min. film, Hotel Chevalier. Schwartzman's Jack seems uneasy when he gets a call from an ex-girlfriend (Natalie Portman) who insists on showing up in his swank hotel room. He draws a bubble bath for her. They flirt and parry and wind up in bed, exchanging dialogue that we hear again, at the end of Darjeeling, as part of a story Jack has written. It's a beguiling vignette that, as Closer and My Blueberry Nights did, shows Portman as a comic actress in fresh bloom. I wish that she, and some of the feeling and wit of the short film, had been in the long one.

Actually, there's a bit in Darjeeling — it lasts just a minute or so — that shows what Anderson is capable of. The camera tracks down a corridor of train compartments; in each is a different character, glimpsed for just a few seconds. The Sikh trainman, the hostess, Peter's wife, Jack's Paris assignation... and Bill Murray, as a businessman seen briefly at the film's opening. It's a gracefully composed series of snapshots into the lives of Darjeeling's subsidiary characters, and it made me yearn to dip more fully into their stories. I wanted to be in their movies more than in the one about the Whitman brothers.

Maybe Anderson could make a film, at least a short, about each of these characters. It'd be fine by me if his collaborator on the screenplays was Owen Wilson. It could be therapeutic for all of us.