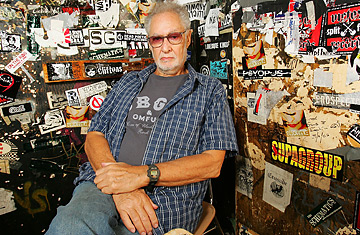

Former CBGB owner Hilly Kristal died August 28, 2007, in New York City

Hilly Kristal, who died Aug. 28 of complications from lung cancer, agreed to a rare interview in November 2006 to discuss the legacy of CBGB, the club he had founded to promote his first musical loves — country, bluegrass and blues (CBGB) — and which in the 1970s and '80s became the official mecca of the underground New York rock scene. By that point, he had been battling cancer for some time, making him noticeably skinnier and less mobile.

When I met with him, it was in an unfurnished office in the back of a storefront on St. Mark's Place, only a few blocks from where CBGB had closed the month before. At 74, weakened and depleted by chemotherapy, Kristal still exuded the charisma that had made him such a lionized figure during New York's punk heyday. He was even wearing dark sunglasses indoors.

He was happy to talk about life after CBGB, the downtown Manhattan club that some say turned punk into a movement and a lifestyle, and helped make names of the Ramones, Blondie, Patti Smith and Television. After the club closed following a much-publicized dispute between him and his landlord, Kristal planned to open another venue, although discussions were on hiatus. Las Vegas and Boston were possibilities, he said, but much still rested on the bottom line. "All I have to do is get a little more money," he said. "Everything takes a lot of money."

He hoped a new venue would further his commitment to helping unknown musicians find a place to play, much as he did in 1973 when he opened up CBGB on New York's seedy Bowery and invited original artists to perform sets — something most established venues in the city wouldn't do. "Clubs didn't let you do that," he remembered. "I guess you could sneak in one or two songs, but if you didn't have a big record out, they didn't want [you]. They wanted covers. They wanted you to play things that people know. I felt originality was the most important thing in rock." It was a feeling shared by the musicians the club attracted, who were searching for a place to play original music. "I felt very good about it, letting them do their own thing," he said. "In any art form, I think that's the most important thing."

Shortly thereafter, Kristal decided to set that belief in stone: cover bands were effectively banned from CBGB's stage. "When I saw there were more and more bands that just wanted to play their own music, and there was no place to play, I didn't say they could play [original music], I said they have to play it," he recalled. "I think it made things more interesting — sometimes a little more agonizing, [but] sometimes more interesting." Interesting was an understatement: CBGB quickly became a scene in Manhattan; Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol, Allen Ginsberg and Paul Simon all rocked out to bands that were signing record deals left and right. Musicians like the Police, Bruce Springsteen and even Alan Jackson all graced Kristal's stage. CBGB became an icon and a brand.

A musician himself, who became a concert violinist by the age of 9 and sang in the men's chorus at Radio City Music Hall, Kristal still tried to play when his health permitted. "When I'm home, I try to play the guitar and my fingers are not good from the cancer, the chemotherapy," he said. "But I'm trying."

After closing CBGB, Kristal packed up much of the club's furniture, equipment and decor and placed it in a Brooklyn storage unit. If he had lived to open another, he planned on making it look as much as possible like the original — tight walls adorned with a cacophony of bumper stickers and concert announcements, a mini lounge area, and the tiniest of stages. In the meantime, he auctioned off artifacts on eBay that didn't make the cut. An 11" x 15" emergency light box decorated with stickers sold for $310. A 12" x 13.5" framed section of CBGB's graffitied wall sold for $493.

Kristal said he rarely let the anger over his club's closing or financial worries overcome his fond memories, especially when it came to Patti Smith, who played CBGB's final concert and is one of the most successful performers to emerge from the club's storied history. "I wanted to enjoy Patti," he said of that last show. "When I think of all the other bands that started, especially with female singers, I think she was one of the biggest influences, maybe the biggest influence." But the memories sometimes weighed heavily. "Even yesterday afternoon I started to feel a little despondent," he said. "You know, no more home. Thirty-two and a half years, it's a home. It's more a home than my tiny little apartment. Everything revolved in my life around making it work and being there. You feel it more afterwards." Kristal said he occasionally walked by the old club — "It's closed," he noted, "the gates are down" — but even that was getting to be difficult for him physically. "Two years ago I could run around. Now I need a cane to keep my balance."

During his decades at CBGB and in this rare interview, Kristal proved that he may not have been the keenest when it came to legal battles or money woes, but he tried, even when his club was taken away from him, to live up to what that "OMFUG" stands for in CBGB's formal name: "Other Music For Uplifting Gourmandizers." Kristal defined a gourmandizer as a voracious eater of music.

"[CBGB] has a lot of good meaning for people: of getting together, of playing music together," he said. "You know it's a very good thing we need these days.

"When people play on the same stage, they don't care who they are. There's a certain respect they have for each other, and they enjoy playing the same stage," he said. "I think the music transcends a lot of things, especially as long as they're allowed to do their own thing."