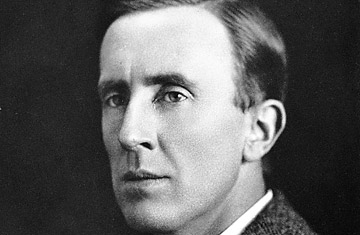

Author J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973).

The Children of Húrin is set in the First Age of Middle Earth, six and a half millennia pre-Frodo, back when Treebeard was barely shaving (Tolkien scholars will know that The Lord of the Rings takes place in Middle Earth's Third Age). The First Age has a different feel to it: it's younger and wilder somehow. The elves, distant figures in The Lord of the Rings, spend more time outside their secret spa-resorts mixing it up with mere mortals. When, in the midst of a huge battle, a balrog rears up and whips down a warrior like it's no big thing, right there in the thick of the press, you realize the rules of the First Age are a little different.

The hero of Children is Túrin (son of Húrin), an aristocratic human who has the good fortune to be raised and trained up by the elves into a bad-ass swordsman. Túrin is good-hearted but flawed: he's irascible, quick to anger and quick to act on his anger — he has a bad habit of killing people before he quite realizes what he's doing (though he's always remorseful afterwards). "Túrin was slow to forget injustice or mockery," Tolkien writes, "and he could be sudden and fierce. Yet he was quick to pity, and the hurts or sadness of living things might move him to tears." A dark cloud follows him, and Tolkien lays on the omens of foreboding: you get the sense that Túrin was born under an unlucky star.

The villain of Children is the cowardly and spiteful Morgoth, who's your basic evil incarnate. Tolkien's baddies rarely have much in the way of personality, and Morgoth spends most of his time squatting in his dark fortress of Angband, casting a shadow over the land and generally making war on all that is just and beautiful. He leaves most of the actual scrapping to his lieutenants, most notably Glaurung, a wingless, wormy and rather sarcastic dragon.

Children is written in Tolkien's full-on high heroic style, which is light on the characterization and sometimes hilariously dorky. (An example, chosen more or less at random: Túrin's helmet "was made of grey steel adorned with gold, and on it were graven runes of victory. A power was in it that guarded any who wore it from wound or death, for the sword that hewed it was broken, and the dart that smote it sprang aside." Et cetera. The book also comes with some pseudo-Blakean illustrations by Alan Lee.) But once you surrender to the richness of Tolkien's vision, the immersive detail of it, the faux-archaic diction barely registers. Children, as a short work, never achieves the towering operatic grandeur of the trilogy, but it's a huge pleasure to be back in Middle Earth, and to see people and places that Tolkien only alludes to glancingly elsewhere. There's plenty of lore for the scholars and superfans, and there's no shortage of elves and dwarves and mighty smiting for the casual fan.

Just heed this warning: The Children of Húrin is a darker, bitterer tale than we're used to seeing from Tolkien. Its hero is proud and imperfect and willful — more Boromir than Frodo — and his story is full of accidents and disasters, poisoned barbs and ruinous betrayals and grievous misunderstandings. Which makes sense: after all, if the good guys had beaten the forces of darkness in the First Age, they wouldn't have been stuck with Sauron in the Third.