|

The Pride of Baghdad takes its premise from the true story of a group of hungry lions that wandered out of the abandoned Baghdad zoo in the days prior to the arrival in the city of the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division on April 9, 2003. Writer Brian K. Vaughan has a reputation for creating superior "genre" comics with clever ideas that are at once funny and suspenseful. His monthly Vertigo series Y: The Last Man, about a world where all the men have suddenly died except for one, rivals TV's Lost as a smart, consistently entertaining work of popular art. Pride starts with an equally clever idea that and makes for an engaging read, but falls short of a being a masterpiece on the ambiguities of waging war for the sake of someone else's "freedom."

The pride in question consists of Zill, the male who still remembers sunsets from the days of being wild; Safa, the older, wizened female; Noor, the younger female who dreams of her freedom; and Ali, the cute cub. As in a Disney movie, the animals have been blessed with the ability to speak to one another, along with the superior intelligence that usually accompanies that ability. However, suspending one's disbelief around such conceits comes more easily with children's entertainment than with a serious consideration of adult themes. I find myself thinking things like, "Does an animal that can speak of heaven need to achieve grace, or is it (he?) born without original sin?" In any case, after the bombs hit the zoo, the once-caged animals blink through the smoke and ask, "Are we dead?" Zill replies, "No. We're free."

The pride wander the empty streets. "I think it's another zoo," says one.

The pride wander the empty streets. "I think it's another zoo," says one. |

Unlike a Disney movie, the story of the lion's new-found freedom is grim, violent and full of danger. Artist Niko Henrichon sets the scenes perfectly with lushly detailed environments ranging from green parkland reminiscent of the jungle to the dusty, empty streets of a bombed-out city. What the highly polished artwork may lack in idiosyncrasy it more than makes up for in its professionalism of production. The sumptuous colors and sophisticated light effects are worthy of a top Hollywood cinematographer. In one memorable scene, Noor chases a group of white horses into a dark, abandoned palace where she comes upon giant mural of a winged lion. We are as startled to see it as she is.

As Zill and the others wander, they begin to question whether the chaos and destruction of this new freedom seems like a real improvement over the limited but safe world inside the cage. But this clever metaphor for the Iraqi people will sometimes get stretched thin by scenes created only for the sake of generating some action. At one point the pride must work together to overcome a ferocious bear. (The insurgency?) While I am as much in favor of an awesome lion vs. bear fight scene as the next guy, it feels like an obligatory fight scene being played out rather than a natural circumstance of the story or intended theme. Still, there are enough occasions of unexpected storytelling, as when the group encounters a bitter snapping turtle on the banks of the Tigris, to make The Pride of Baghdad an engaging and well-meaning read, if not always the subtlest of metaphorical storytelling.

|

Where Pride lives or dies by the quality of its fiction, The 9/11 Report deals in cold, hard facts and means to present them in an attractive, well-organized and easily readable way. The Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, a.k.a. the 9/11 Commission Report, became a best-seller when released in July 2004. Now its comix adaptation has become a best-seller too, reaching the top ten non-fiction paperbacks list two weeks in a row. The result of months of investigation, including thousands of interviews, the report and its comix adaptation examine the origins of the plot of September 11, government efforts (or the lack thereof) to foil the plot, a timeline of the events of the day, and conclusions about what went wrong and how be better prepared for the future. The 585-page original has been reduced to 130 pages by Sid Jacobson, who, along with illustrator Erni Colon, boils down the contents into digest form without losing the substance.

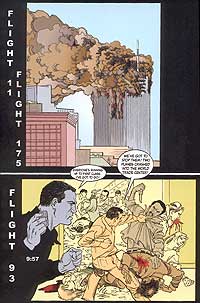

Unlike the recent TV movie The Path to 9/11, which turned The 9/11 Report into a narrative that received sharp criticism, the comix adaptation adheres to the non-partisan tone of the original book — for better or worse. For the better it avoids messy editorializing. For the worse it loses the engagement of telling a single story. It begins with what journalists call a "tick-tock," a minute-by-minute accounting of the hijacking of the planes. Cleverly, Jacobson and Colon use the graphic abilities of the form to show each plane's story in four parallel timelines running across the pages. The appalling lack of communication can thus be seen on a single page as United 93, delayed on the ground by nearly 45 minutes, only receives warning of multiple hijackings at the same time that the North Tower burns, the South Tower is struck and American Airlines 77 is taken over.

Flight 93 battles the hijackers as the Twin Towers burn in 'The 9/11 Report'

Flight 93 battles the hijackers as the Twin Towers burn in 'The 9/11 Report' |

From the tick-tock of the ill-fated flights, The 9/11 Report steps back to examine the origins of Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda, various U.S. administrations' treatment of the terror threat, and the way the terrorists organized the September 11 attacks. Though not always completely clear in the details, the gist comes through well enough: a complete failure by multiple administrations to take bin Laden and terrorism seriously. It includes such devastating truths as "[The attack] was carried out by a tiny group of people with trivial resources operating from one of the poorest, least industrial of all nations... In some ways they were more globalized than we were." Those looking for a neutral primer on the background of the events of 9/11 will probably not do any better than this handy book.

Those looking for Art should go elsewhere. Unlike the original Commission Report, which received as much literary as political criticism, the comix adaptation has the dry sensibility of a typical governmental report. Ernie Colon, a journeyman cartoonist who has worked on countless mainstream comic projects, provides highly competent if not very memorable illustrations. Occasionally his good guy vs. bad guy background seems to unconsciously pop out, such as when he depicts George W. Bush, who stands at 5'11" according to the White House website, as the tallest guy in a room, or when one of the terrorists looks more like he should be searching for his missing chromosome than plotting the single worst attack on U.S. soil.

Still, when the simple, thoughtful language of the original report comes through, it can be moving. This is most particularly true during the chapter covering the rescue attempts of the North and South towers. "Then the second plane hit," reads one panel, depicting the deadly second impact. It continues, "At 9:03:11, the hijacked United flight 175 hit the South Tower from the South, crashing through the 77th to 85th floors. And the most complicated rescue operation in history instantly doubled in magnitude." If nothing else, readers should remember a single panel, depicting a firefighter carrying a wounded woman. It reads, "The lesson of 9/11 for civilians and first responders can be stated simply: in the new age of terrorism they are the primary targets... We must plan for the next attack. This is perhaps the best way to honor the memories of those we lost that day."

Each in their own way, The Pride of Baghdad and The 9/11 Report deal with the most serious events in the U.S. at the turn of the millennium. Where one takes a metaphorical, artistic approach the other shuns art in favor of blunt non-fiction. Both are thought-provoking and timely. The 9/11 Report in particular has broken ground by using comix to further popularize a critical document for the public good. Its success will doubtless result in a flurry of OMB and Federal Reserve adaptations. We look forward to them.