|

Miriam Katin's We Are On Our Own (Drawn & Quarterly; 128 pages; $20) can be read in less than hour, thanks to its page-turning true tale of life and death during the Nazi occupation of Hungary. Still, the return on such a short investment of time is an unforgettable tale of a mother's courage in the face of nightmarish cruelty. Along the way, it explores the precarious nature of religious faith, which for some can be stretched too thin for suspension.

We Are On Our Own recalls Katin's mother, Esther Levy, who takes care of two-year-old Miriam alone in Nazi-occupied Budapest while her husband fights in the Hungarian army. The book opens with the urbane and middle class Esther sharing coffee with her best friend, discussing how the Nazi death trap was closing in. "I received an order to hand over the dog today," she says, as Miriam feeds ice cream to little Rexy. First denied their pets, the Jews of Budapest are soon commanded to leave behind all their possessions and report to the ghetto. Hearing rumors of round-ups from which no one returns, Esther buys fake papers that identify her as a village servant girl with an illegitimate daughter. She plans to flee the city, burning every personal identifier before she does. This includes, notably, the family Bible.

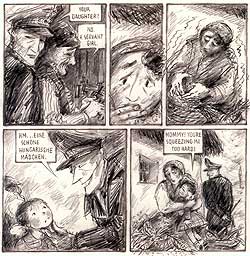

A Nazi Kommandante sets his eyes on the author's mother, in Miriam Katin's 'We Are On Our Own'

A Nazi Kommandante sets his eyes on the author's mother, in Miriam Katin's 'We Are On Our Own' |

Once outside of the city, Esther stays out of the way by living on a farm. Trouble comes when the local Nazi Kommandant spies her. Suspecting she is a Jew, instead of turning her in, he forces her to become his mistress. Soon this horror gives way to another as the Nazis retreat from the advancing Russian troops. The Russian's vodka-fueled barbarism sends Esther fleeing into a snowstorm, pulling Miriam behind in an open suitcase. This intense sequence becomes the book's dramatic and thematic climax. While some may see the hand of a benevolent God in sending the snows and a shelter to protect them, for Miriam the site of a dog shot by the soldiers brings her to a different conclusion.

Between these scenes of grey-toned horror we witness flashes of Miriam's life, decades later, fleshed out in full color. Her son has reached the age of being entered into Hebrew school and Katin struggles with whether to send him, "to be with our own kind," as her husband says. "You mean to separate. Again," she replies. These flash-forwards reveal the lasting effect on Miriam, who barely remembers any of the events depicted in the book. For her, leading a purely secular life is the only answer to the atrocities she and her mother experienced. It's a bold theme in an American culture more used to books with theological bromides (see the Chicken Soup series) than existentialism.

You wouldn't guess that We Are On Our Own is Katin's first graphic novel. Having illustrated children's books and worked in animation, Katin has had a lifetime of practicing her visual narrative skills. Working mostly in graphite pencil, the monotone palate evokes the grey days of Nazi rule in a past desaturated of color. Instead, Katin uses shading to create detail and rich texture. She keeps the layout simple, with rarely more than six panels per page. When the action heats up, characters will burst out of their borders, making the page more dynamic.

Thankfully, in the second half of the book, Katin reminds us of life's kindnesses as the other side to life's cruelty. Still alive at the end of the war, her father returns to Budapest in search of his family, only to find them long gone. He begins his own parallel journey as Esther and Miriam take up residence with a family friend, the lonely scion of a local industrialist, whose family are all dead. A French governess provides a comic and blissfully domestic antidote to the earlier scenes of outrageous hardship. As the story winds up, it concludes with a bittersweet scene of love lost and found. Even as fiction it would be one of the best stories I've read in the last year, but as a memoir it leaves you speechless. Miriam Katin's We Are On Our Own should not be missed by anyone with an interest history, the nature of love and faith or anything human in between.

|

Alison Bechdel's Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (Houghton Mifflin; 232 pages; $20) couldn't be more different from We Are On Our Own, yet it shares a focus on one parent's story. Bechdel zooms in on her enigmatic, controlling father, who, we learn early on, was an apparent suicide during the author's late teens. Now in her forties, Bechdel has gained a strong reputation for her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, a long-running weekly strip currently up to its eleventh collected edition. For Fun Home, her first long-form work, Bechdel has created a surprisingly sophisticated memoir that subjects her own life to the close reading one would dedicate to a work of literary fiction.

When Bechdel quickly reveals both her father's premature death and that he led a secret life as a deeply closeted, shame-filled gay man, it comes as a shock. What author would give away both a natural narrative climax and the key to a person's mystery right at the beginning of the book? The answer is: the kind of author not interested in easy drama and simplistic explanations. In a series of chapters that more or less follow Bechdel from young childhood until her college years, the book traces her father's story and her own in the context of his secret. This way she can parallel her life as a lesbian who healthfully revealed her inclination shortly before her father's death, only to discover his inner life as a corrupted version of her own.

Alison Bechdel examines her father in 'Fun Home'

Alison Bechdel examines her father in 'Fun Home' |

One of the most memorable portraits of any character yet seen in this medium, Bechdel paints her father as a classic "closet case." An obsessive home decorator and control freak, he challenges any gender non-conformity he discovers in his children, for example making the young Alison, whose playground nickname is "butch," wear a barrette when she doesn't want to. He also runs the family business, a funeral home, which gives the book its snarky double-entendre title. Far from fun, thanks chiefly to the father's quashing of all affections lest the "bad" one be exposed, Bechdel compares her home life to an artist's colony rather than a family. "We ate together but were otherwise absorbed in our separate pursuits." One of these pursuits, to her father's credit, was a deep appreciation for literature, perhaps the only love he managed to pass on to his daughter.

This manifests itself throughout Fun Home, which ranks as one of the most self-consciously bookish graphical works yet published. Many of the chapters use a canonical literary work as a central metaphor and reference point. Often as tangentially associated with homosexuality as her father, the works cited include The Greek Myths, Camus's The Death of Sisyphus, Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, The Great Gatsby and eventually back to the Greek myths by way of James Joyce's Ulysses. The "Ulysses" chapter takes place near the end of Fun Home, when Bechdel must read it for course credit. At the same time she comes out to her parents, though her father says nothing about it or his own truth. "Like Stephen and Bloom at the National Library, our paths crossed but did not meet," she writes. Her mother reveals the truth a few weeks later, to her daughter's utter surprise. "I'd been upstaged," she writes, "demoted from protagonist in my own drama to comic relief in my parents tragedy." It's a typically clear-eyed line in a book crammed with such insights.

Still, Fun Home's personal exegesis can read a little too much like a personal essay with illustrations, rather than a fully organic work of graphic literature. The author often insists on telling us about an event, with critical hindsight, in a running narration over the tops of panels that simply duplicate what you read. For example, in one scene Alison must help her father hang a mirror in her already over-decorated room. "I hate this room," she says in the panels. "When I grow up my house is going to be all metal, like a submarine." This says it all. The text, "I grew to resent the way my father treated his furniture like children, and his children like furniture," feels superfluous. Bechdel draws in a clear, moderately realistic black and white style with a cool, greenish-grey wash creating highlights and depth. Though maybe not the most visually memorable of cartoonists, Bechdel's conservative approach has clarity on its side. She could have trusted it more. As a test, try reading it without the narration and see how much you get without it.

Though it may be a bit wordy, Fun Home's depiction of a love-starved childhood leaves a lasting impression. Bechdel recalls her period of OCD, her father's arrest for buying an underage boy a beer, and family trips accompanied by male baby-sitters with as much of a sense of their tragedy as their dark comedy. She will slip in the occasional sick joke amid the scenes of frustration and bewilderment. Loaves of Sunbeam bread repeatedly make appearances, for example, echoing her father's eventual demise by being run over by a truck from that same company. Gradually, as Bechdel adds so many layers of history and nuance to her father's personality he changes from Ogre to tragic casualty of self-denial. Conflating the worlds of personal history, "queer studies," and literary criticism, Alison Bechdel's Fun Home can be enjoyed as any of those, or just as a smart, insightful, funny/sad story about growing up.