|

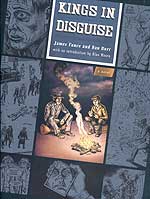

An unusual and anomalous work in many ways, it remains unique in the oeuvre of both the writer (Vance) and artist (Burr), who never worked together again and neither of whom went on to produce much of anything even remotely as interesting. [Update: they are now working on a sequel, I am told.] Kings originates from Vance's days as a playwright of Depression-era, ash-can style dramas. Set in the early 1930s, the book follows the adventures of the 12-year-old Freddie Bloch, a working-class kid forced by circumstances to hit the railroad tracks of America, and enter the world of the destitute and homeless. Using convincing period detail and mixing it with fresh takes on the tropes of Depression-era dramas (breadlines, hobos, strikes, etc.) Kings in Disguise tells a coming-of-age story like none other in the medium.

A sort-of reverse Grapes of Wrath, Kings starts in an agricultural town in southern California and works its characters East. Freddie, the slightly dreamy younger of two brothers whose mother has died, sells his father's used liquor bottles to fund his escapes to the movies. It may surprise some readers to discover Freddie is Jewish when plans for his Bar Mitzvah are mentioned: Unlike more familiar Depression-era stories of being Jewish in America, where characters struggle with assimilation in an urban ghetto, Kings tells a less common story. Freddie seems totally integrated into his small town, his Jewish identity becoming even less important when his father vanishes and his brother gets caught stealing for grocery money. Once Freddie tumbles down a slope into a hobo camp, he enters a world where impoverishment erases the distinction of being Jewish. By the end of the book he realizes that his 13th birthday has been completely forgotten.

Freddie and Sam in Kings in Disguise

Freddie and Sam in Kings in Disguise |

At the hobo camp Freddie meets Sam, AKA "The King of Spain," an older drifter with several past lives. He's a bit of a cut-up, this self-proclaimed monarch of the boxcars, and he brings out Freddie's nascent personality. Their relationship forms the heart of Kings in Disguise, turning the book into an unusual buddies-on-the-road story. Over the course of the story Vance keeps the relationship finely tuned by changing its nature from the beginning — Freddie needs a mentor and Sam needs a purpose in his life — through the end, as Sam becomes increasingly ill from being on the road. The plausibility of this bond has as much to do with the artist Dan Burr's sensitive and realistic portrayal of the characters as much as Vance's sharp writing. Burr's black and white drawings are as powerful at depicting emotion as they are of depicting period and place.

"Used to be, when times got too hard to take... you could go west," says Sam to Freddie during their first long night in a boxcar. But now, he says, "there's no place left to escape to, except places we already run off from." Sam's pessimistic take on the future also pertains to Freddie's plan to travel to Detroit in search of his father. This odyssey takes them across America's underclass, from farmsteads to cities and back again, in a swath that includes all colors and backgrounds.

Word of the police sends the homeless running

Word of the police sends the homeless running |

This is no Horatio Alger story of a boy picking himself up from nothing. It is far closer to something Upton Sinclair would have written. A major subtext of the book is Freddie's maturity as a person coinciding with his political awakening. This begins during an exciting sequence when he finds himself caught up in a protest against the Henry Ford plant. Like a scene from an Eisenstein movie, the protesters face Ford's gun thugs by singing the International, leading to a horrific massacre. Later Freddie and Sam join a group of outcasts working together to put a farm back on its feet.

Though Kings has a political point of view, it never comes off as dogmatic. Vance is too dedicated to telling a good story and, helped by Burr's finely detailed characterizations, it never loses focus on interior lives of the central characters. It even occasionally breaks the verisimilitude for a dream sequence. By the end, Kings in Disguise delivers a heartwarming story set in a cold world.

One of the medium's lost treasures, James Vance and Dan Burr's Kings in Disguise is a graphic novel in the truest sense, creating a fictional world with strong characters, Great Themes and literary ambition. It deserves to be read by anyone with an interest in both history and great comix storytelling.