|

The Quitter (DC/Vertigo; 104 pages; $20), a hardcover book illustrated by Dean Haspiel, represents Harvey Pekar's first major work of original material since the release of the film American Splendor, based on his comix series. As anyone who watched that splendid movie knows, Pekar led a fairly unremarkable life as a Cleveland file clerk until he decided to turn that very mundaneness into comic art. Hiring others to illustrate his non-fiction vignettes of such quotidian occurrences as starting a car in the winter or talking with co-workers, Pekar's stories were driven by his intensely cranky, neurotic, highly-intelligent and, above all, hilarious personality. But the one thing Pekar never explored, until now, was how he got that way. The Quitter takes Harvey back to his childhood with the candor and unsentimentally that we have come to expect from his regular series.

Pekar grew up as the child of Polish-Jewish immigrants in Cleveland during the 1940s and 50s. As a result, much of The Quitter involves the classic American literary theme of assimilation. Though extremely popular in other mediums, this theme, again, has gotten little attention in comix except obliquely, through such genre works as Seigel and Shuster's Superman character. Thanks to Pekar's obsessive self-examination and what he calls his "trick" memory of near perfect recall, The Quitter takes its place as a top example of the New World Experience in graphic literature (see also the outstanding Four Immigrants Manga).

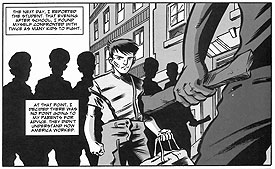

The young Harvey learns about America the hard way

The young Harvey learns about America the hard way |

A major part of the book focuses on Pekar's realization of how different his own experience of America is from that of his parents. One early scene shows him enduring a punishing street payback after following his mother's advice about turning in a kid that stole his hat. "At that point, I decided there was no point in going to my parents for advice. They didn't understand how America worked." So begins the author's lifelong alienation from his parents whom he loves and respects but from whom he gets little of what he needs.

Dean Haspiel renders Harvey's story in stylish black and white art rooted in the dynamics of superhero books but with an alty personality all its own. If the book has a fault, it's that too often the artwork gets reduced to merely illustrating the words instead of taking over the narrative drive. But at least Haspiel has plenty of opportunities to display his chops in depicting fight scenes. Longtime fans may be shocked to discover what a scrapper the younger Pekar was. A large part of the book explores his use of violence as a way to gain respect and attention from his peers, something he felt he never got from his parents. Other, ultimately self-defeating behaviors also manifest themselves. His drive to excel at everything eventually makes Pekar so deeply fearful of failure that he quits anything that challenges him: school sports, the navy and college. Among other things, The Quitter becomes a devastatingly sharp psychological portrait of how early adaptive childhood behaviors can eventually turn against us.

As Pekar gets older in the book, The Quitter returns to one of the main themes of all Pekar's work: the redemptive power of art. During high school he discovers both a passion for jazz and a capacity for critical analysis. So, while toiling away at such unchallenging jobs as playground supervisor, beer inspector and file clerk, Pekar finds his self respect through writing about jazz for such publications as The Jazz Review and Downbeat. Later, of course, he also begins working in comix, a move he goes into briefly at the end. By the time it concludes, The Quitter will have you engrossed by its unpretentious and penetrating examination of the author's experience as a first-generation American, and, in an unexpected way, the embodiment of both this country's brutality and its promise.

|

Told from two generations later and a world apart, Shane White's North Country (NBM; 96 pages; $14) seems superficially completely different from The Quitter. Where Pekar explores the life of a Jewish immigrant's son in post-WWII urban America, White's experience is that of an nth-generation non-denominational Christian growing up as the child of Vietnam-era parents in the farmland of upstate New York. In spite of this, both books share themes of violence, the legacy of parental neglect, and the power of personal expression to move people beyond their crushing circumstances. For a first-time graphic novel author, Shane White exhibits a remarkable talent for the form, delivering a shattering and memorable portrait of abuse and reconciliation.

As the author flies from his home in Seattle back to visit his folks, various objects or sensations — an orange backpack or the smell of fast food — trigger flashbacks. These mostly center on the terror of living with an alcoholic, abusive father and a beaten mother. White masterfully evokes the milieu of the early 70s and hardscrabble folks that got married too young and gave up too much too soon. Fights would get bad enough that Shane spends stretches at a time with his grandmother, who takes him with her to the bar where she works. While she flirts with customers, making him "feel weird," Shane drinks "flat cokes" and eats "smoke-flavored pretzels." Such details become a hallmark of North Country, bringing scenes alive. One sad and telling sequence finds Shane delighted by an old piano left in a house into which his family moves. "But the music didn't last," he writes over a frame of his father smashing the instrument. "To make more room, they dismantled it into scrap."

Shane White faces a brutal upbringing in 'North Country'

Shane White faces a brutal upbringing in 'North Country' |

Transitioning back and forth from the present to the past with clever visual queues, White provides a coolly detached and analytical narrative over emotionally wrenching scenes. Rendered in full color, using a myriad of different styles, North Country takes full advantage of its graphical opportunities to enhance the story. Only a handful of comic artists have the self-confidence to switch from a sad scene of failed escape rendered in the old-fashioned color dots of past comics, to a harrowing red-hued sequence of a kiddy party interrupted by a berserk relative who starts a shoot-out through the window. Seemingly out of nowhere, Shane White has arrived with a grossly huge talent for drawing and a keen knowledge about how to use the form of comics to best editorial advantage.

Like The Quitter, North Country focuses on depicting the young author's various coping mechanisms, like playing dead under various pieces of furniture and out in the deep-piled snow, as well as the psychology behind them. Desperate for attention and approval, like Pekar, White both gets into fights and excels at school. Also like Pekar, at a crucial point a third person takes an interest in his special talents. For Pekar it was a New York jazz critic. For White, a woman at school encourages his talent at drawing, giving him a sense of purpose. Eventually, as Shane begins to be more independent, his fear of his terrifying father collapses. Though the ending doesn't provide us with the desperately desired confrontation scene, and wraps a little too quickly, a vague note of forgiveness, but not forgetfulness can be found.

Harvey Pekar's The Quitter and Shane White's North Country both tell powerful coming-of-age stories from completely different places and times. In spite of that, their similarities make for striking comparison reading. While either would make a fine addition to this growing sub-genre, to have both in one month feels almost gluttonous.