|

North Korea seems to have taken over the space in America's collective consciousness formerly occupied by the planet Mongo. Created by the brilliant cartoonist Alex Raymond, the distant Mongo, as ruled by the diabolical Ming the Merciless, a jaundiced and slant-eyed despot, perpetually plotted our destruction until Flash Gordon foiled its schemes. Substitute Kim Jong-Il for Ming, and nuclear weapons for invading spaceships, and you have a pretty good approximation of America's poor sense of an extremely closed and apparently hostile other world. How appropriate, then, that another kind of comic would be the most readable attempt at exposing the life and culture of this otherworldly place. However, a vexing question hangs over the book: does it illuminate or perpetuate the stereotyped "Oriental" image Americans have of Asia, and North Korea in particular?

Pyongyang chronicles the two months that Guy Delisle, a French-Canadian animator, spent in North Korea in 2001, prior to September 11, supervising work on a French TV cartoon outsourced to inexpensive North Korean animators. His expectations are indicated by two of the items in his baggage: a copy of George Orwell's 1984 and a clandestine AM/FM radio. Those expectations appear to be immediately validated when, at the airport, he can't make out anyone's face because the lights are off. Delisle soon learns that the lights stay off throughout most of the city, to save on power, except when they illuminate huge monuments dedicated to the country's father-son ruling dynasty. This lack of illumination, except for the dear leaders' visage, becomes Delisle's natural running metaphor for the country's blinkered culture.

Guy Delisle takes a stroll in 'Pyongyang'

Guy Delisle takes a stroll in 'Pyongyang' |

Because of the extreme limitations on where foreigners may travel, the bulk of the book takes place in Delisle's hotel, and at the various official landmarks he is encouraged to visit, almost all of which pay homage to the state or its leadership. As a result the book reads as a series of sharply observed and funny/scary anecdotes on the life of a foreigner in what may be the most hyper-controlled society in the world. One typically smart sequence examines the ubiquitous side-by-side portraits of the leader Kim Jong-Il and his dead-but-technically-still-in-charge father Kim Il-Sung. They appear in every single room, except in the shitters of course. He notes how both men have been made to look nearly identical, "same size, same age, same suit. That way nothing ever changes. It's always the same head at the helm." He even notices that the portraits always tilt slightly downward, preventing glare and intensifying the gaze.

An animator and graphic novelist with a few other books behind him (all in French, including another travelogue, Shenzhen, about his time in China) Delisle's drawings have a lively cartoonish quality and an elegant, easy-to-read design. The black and white artwork has been done mostly in pencil, with soft shading, capturing a grayed out world devoid of color. His simplified characters inhabit more detailed environments, in the classic European bandes dessinee style, but with Delisle's own spin. Visual jokes also lighten up the grim totalitarian atmosphere. One panel imitates a Sunday comics puzzle, depicting a police lineup of ordinary-looking North Korean citizens with the quiz, "Which one is the spy?" The answer, upside down, reads, "No. 6 because he is not wearing his official Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-Il pin."

Mr. Sin says: "It is always interesting to get another perspective on things!"

Mr. Sin says: "It is always interesting to get another perspective on things!" |

Delisle gets assigned an official guide, Mr. Kyu, which all non- diplomatic foreigners must have, and a translator, Mr. Sin. These two become the only North Koreans that Delisle is allowed any extended contact with. In spite of this they remain — and I am going to use a loaded word here — inscrutable. Of their personal life we learn nothing. Of their feelings and opinions we learn almost as little, except when Mr. Kyu unwittingly borrows 1984, which Delisle slyly describes as "science fiction." Mr. Kyu later returns the book nervously but says little about it except that he "doesn't like science fiction." The apparently humorless Mr. Sin says little more than party dogma. He becomes emotional only during a visit to the huge museum dedicated to Papa Kim, where visitors must wear comical giant slippers so as not to scuff the floor. "What a great and generous man!" Sin exclaims at the ludicrous and nearly endless display that concludes with a wax replica of Kim Il-Sung before which all visitors must bow.

During one short sequence, Delisle asks himself the crucial question: "Do they really believe the bullshit that's being forced down their throats?" Unfortunately, it's a question that Delisle never answers. Unlike the work of Satrapi and Sacco, who can present full, rich characters that bring the complexities of distant cultures to life, Delisle remains at a constant distance. Of course the blame for this cannot be put entirely on the author. North Korea's culture of fear systematically and deliberately prohibits foreigners from gaining any kind of truthful access to its citizens. Yet one still cannot help but wonder about Delisle's own, unstated and unexamined prejudices that may have prevented him from fully accessing these people. Pyongyang's depiction of North Koreans as strange, weak (in their inability to critically examine and overthrow an utterly corrupt government) and exploitable by the West fits an unfortunate pattern of past such depictions of Asians. How much of the book's depictions come from Delisle's own cultural expectations? The answer remains debatable. Many of the things he highlights as particularly weird or objectionable have arguable counterparts in the west — something the author never examines.

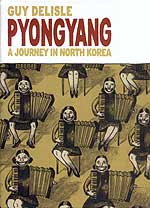

Take the cover image, for example. It depicts a scene in the book where Delisle visits the "Children's Palace," a school for gifted children. He depicts row upon row of near identical girls playing an accordion concert with rictus grins across their face, "as though the thin veneer of their smiles were proof that these young prodigies were flourishing here." Yes it looks horrible, but no more so than one of those frightening children's beauty contests made popular in the southern U.S. Or on a broader scale, Delisle does an outstanding job of depicting North Korea's relentless culture of fear and hostility, where "volunteers" keep unused roads tidy, where people vanish and their fate is unspoken-of and where the few forms of entertainment relentlessly depict the U.S and Japan as cruel torturers bent on destroying North Korea. Yet don't most U.S. citizens live in a different kind of perpetual fear? Both homegrown gun violence and international terrorism have literally raised our "threat level" to red. And didn't the current U.S. President characterize North Korea as part of an "Axis of Evil," a rhetorical flourish worthy of Flash Gordon?

In spite of the limitations placed on him, Guy Delisle's Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea provides a fascinating tour of this demonized, closed-off country in a highly readable and entertaining way. What one wishes for, but never gets from Pyongyang, is how the author feels changed by the visit or how he reflects upon his own culture in the context of North Korea. Even so, while this smart and funny book may not dispel the West's fears and prejudices about North Korea, and may even confirm many of them, it will at least give its readers something a little more real than the Mongo-like vision perpetuated by politicians.