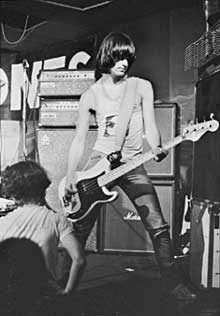

Joey Ramone, Cincinnati, 1977

(2 of 3)

CBGB and the birth of punk

CB's is still there, though I don't know anyone who still attends the events. It's a long club with a bar on the right starting a few feet after you walk in the door, with a raised seating area on the left. The raised area terminates at the soundboard; the bar stops just opposite and the space opens up a bit. Maybe another 30 feet or so through some tiny scattered circular tables there's a stage just a few feet off the floor. Hanging from the ceiling, massive monitors flank it. On the far left a narrow passageway leads to the dressing room and the stairs going down to the most famously disgusting restroom in New York City.

In the neighborhood around CB's, the old Lower East Side of New York, rents were cheap. Lofts could go for one or two hundred bucks, apartments for less. The cheap rents and the dope (which was everywhere, three dollars a bag, with 50 or 60 people lined up on 2nd St. and Avenue B waiting for the dope store to open every morning) attracted the fringe players, the ones who couldn't handle the tedium in Queens or New Jersey or suburban anywhere. From this crowd of disaffected youth emerged our players, and the stage was CBGB.

Hilly Kristal opened the place in '73 and had trouble drawing a crowd. The space had formerly been a typical Bowery bum bar, one of dozens in the neighborhood, opening at 10 in the morning with a few guys from the flophouse standing anxiously at the door. The original hippie concept was to fill it with "Country, BlueGrass, and Blues" (hence the initials appearing on the club's tattered canvas awning) and other American genres that only become exotic when they show up in NYC.

Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine, New York Dolls fans who had recently put together a band called Television with poet Richard Hell, saw the place walking to the bus stop on their way to a Chinatown rehearsal. As Hell says in "Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk": "Where is a bar where nothing is happening? With nothing to lose if we tell them to let us play there one night a week?" They approached Kristal with the idea of doing a series of weekends at CB's, so the band might connect to the space like the Dolls had connected to the Mercer Arts Center. Kristal went for it.

Fifteen or 20 people showed up but the momentum slowly built. Patti Smith showed up next, a local poet with advanced show-biz genes, just beginning to build her legend by knocking them dead at the St. Mark's Poetry Project. With guitarist Lenny Kaye (read his tribute to Joey here) and band, she was added to the weekend lineup and for the first time, the place was packed.

Within months, The Ramones became CBGB punk legend number three.

Four guys from Queens

Dee Dee, Johnny, Tommy and Joey all shared the same invented last name, borrowed from the "Paul Ramon" alias Paul McCartney used to register at hotels. It meant nothing, and they claimed nothing for themselves: They were like all the rest of us. For years Joey and Johnny would tell fans, "We suck. You can play better than us; anybody can play better than us. Start a band." After their legendary July 4th, 1976, Roundhouse concert in England, it seemed like every member ot the audience — which included the guys soon to form The Sex Pistols and The Clash — took them up on it.

At first they could barely play their instruments, and the shows were unorchestrated chaos. In the era of stadium rock, of "Frampton Comes Alive", the Ramones were boys from the neighborhood, not glamorous, not rich, not savvy, not even clean. They were the antithesis of the prog-rock pomp of Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer, the opposite of everything the industry types were claiming we wanted. The Ramones look — long Betty Page bangs hiding the eyes,black leather jackets, ripped jeans, white tee-shirts, and sneakers — said it before you heard a note: "We're Against It".

(photo by author)

Dee Dee Ramone, Cincinnati, 1977 |

They were all from Forest Hills in Queens. Dee Dee hustled for dope money on the corner of 53rd and Third, on the run from a desolate Army-brat childhood in Germany. When he couldn't get dope he would sniff glue. He would do anything, take any kind of drug. I remember seeing him on St. Mark's Place after he left the band, hair short and spiky, in skintight Spandex pants that looked left over from some mall scene of years before. He was thin, "on the heroin diet" as we used to say. Somehow he survived, fought off the dope, wrote a book about it: "Poison Heart: Surviving the Ramones".

Johnny worked on construction projects when he wasn't playing his guitar. He was the organized Ramone, running the practices, insisting on getting it right, absolutely straight-edge on tour with no drink or drugs and an early bedtime. There was always a dark side to Johnny; he seemed tightly wound, intense, sometimes downright nasty. In 1983 he got into a fight over a woman with an obscure punk musician; he was repeatedly kicked in the head, had brain surgery, almost died.

Tommy was the drummer, the intellectual of the band who started as the manager and became the producer, running the sessions that created the first album for $6,400 in three days. (The studio used was in the rafters of Radio City Music Hall, directly across the street from where I write.) He created a streamlined, densely layered guitar attack that Chris Thomas got down cold a couple of years later on the mammoth Sex Pistols debut LP, "Never Mind the Bollocks".

And then there was Joey.

Joey Ramone

Joey was a gangling glandular freak with skin like milk, thin but with wide, girlish hips, topping out at 6'5" or 6'6". He was probably the oddest-looking physical specimen to ever front a successful rock band. He never looked healthy, always pasty and white like something hidden from the sun for a long time.

I have never seen a picture of Joey with his long legs straight; they were always bent in punk contraposto. When he sang his stance was unique: one hand always wrapped around the mic, which was always on a stand, the stand usually bent toward the audience. The other hand was held close, fist clenched, or up and moving in tight gestures that never strayed far from Joey's side. One leg would be thrown forward, Joey's whole frame resting on it, looming over the edge of the stage, over the heads of the fist-pumping fans.

He was fan of Phil Spector's girl groups, a huge Beatles and Brit invasion fan, an intense radio listener who absorbed everything in the AM Top 40 between 1963 and 1969. Before the Ramones he was a glam-rocker, another New York Dolls fan. He would hitch rides on Queens Boulevard in a custom pink jumpsuit and thigh-high boots to play with a band called Sniper, finally getting his ass kicked one night like everyone who knew him was afraid would happen. Even after becoming a Ramone he always wore '60s-style elliptical specs, hiding what I always imagined to be pink mouse eyes behind colored lenses.

More than anyone else in the band, Joey was the fan, the one most like his audience. He was always approachable, always nice, always showing up at odd times around the East Village. My wife (a punk rocker herself) recalls seeing him at 4 a.m. one night at St. Marks' Pizza, a woman under each arm propping him up, his eyes hidden behind red lenses. He didn't like drugs; he drank, finally hitting rehab along with the second Ramones drummer, Marky, in 1983.