|

As he got older, two threads in Eisner's work became increasingly prominent: Jewish identity and the urge to use his work to make a better world. The Name of the Game, from 2001 (see TIME.comix review), cast a family melodrama in the little-seen world of turn-of-the-century Old Money New York Jews who live in town houses. His 2003 book, Fagin the Jew, took Dickens' famous Oliver Twist character and invented a fuller biography for the character, with the intention of dispelling one of literature's most potent defamatory stereotypes. When I interviewed Eisner about Fagin he described the book as a "polemic." In his acknowledgments to The Plot he uses the word again, but this time it is even more applicable. Carefully researched, with introduction by Umberto Eco, reference notes and an afterward by a professor of political science, The Plot examines the history and hydra-like endurance of a repeatedly confirmed forgery that purports a worldwide Jewish conspiracy.

Presented as the results of a secret meeting of Jewish leaders laying out 23 protocols for the supposed Jewish takeover of world governments, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion first appeared in Russia in 1905. Divided into roughly three parts, The Plot begins as a kind graphical literary biography, tracing the life and influences of the real author of Protocols, Mathieu Golovinski. A seedy, low-level aristocrat, Golovinski distinguished himself with the Tsarist secret police as a lawyer with a talent for fabricating evidence against accused enemies of the state. Eventually exiled to France, he was tapped to produce a document that conservatives in the Tsarist court hoped would smear the nascent revolutionary movement as a Jewish conspiracy.

The second third of The Plot turns into a minor detective story as a correspondent for the London Times discovers the similarity between Protocols and a nearly forgotten French parody of Napoleon III. A major portion of The Plot compares passages from both sources in an effort to expose the obvious similarities and outright plagiaries, a comparison that the Times used to declare The Protocols a fake in 1921. The final, melancholy third of The Plot examines the enduring virus of Protocols, which, in spite of numerous, incontrovertible findings of being wholly forged, continues to be published the world over as truth. Eisner puts himself in the book, as the saddened pursuer of history who confronts a student group in San Diego touting Protocols as evidence of Jewish influence. The book ends on a vaguely philosophical note about the nature of prejudice and truth.

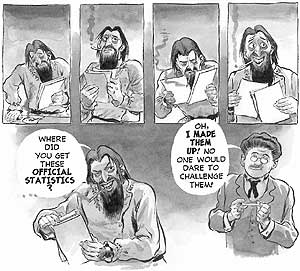

Golovinski (at right) pleases his anti-Semitic boss in Will Eisner's "The Plot"

Golovinski (at right) pleases his anti-Semitic boss in Will Eisner's "The Plot" |

In spite of its admirable ambition, The Plot doesn't perfectly gel into a masterpiece. It suffers chiefly from a problem I have found in many of Eisner's graphic novels: a sometimes-fatal distrust of the audience. Expository dialogue, repetitious action and one-dimensional characterization make The Plot feel more like a lesson than a deeply involving story. In the biographical first third, for example, character development never goes beyond stereotype, as if giving Golovinski more than one dimension would confuse us. One scene depicts a young Golovinski stealing his mother's necklace for no apparent purpose. Presumably fabricated, it reads like scene of cheap melodrama designed to incontrovertibly establish the nefarious nature of an antagonist.

The pace of the book also changes abruptly. After a long narrative section the book suddenly stops cold for 15 pages while it compares passages of the French book and Protocols (which, like most extremist tracts, makes for tediously dull reading.) Subtlety and complexity have been hijacked by good intentions.

The art too, is a lesson in how and how not to make comix. Eisner's early drawings practically defined expressiveness in cartooning. The Spirit introduced the aesthetics of what would eventually be called film noir into the comics of the 1940s. But later, Eisner's work became almost too expressive. While masterfully drafted, there is a whiff of mothballs in the way Eisner's characters mug their emotions, evoking a time of pre-Method overacting. They don't just give conspiratorial looks, they leer with venality. They don't just argue with conviction, they gesticulate wildly. Again, Eisner clearly doesnt think an audience will "get it" without using a visual sledgehammer.

In spite of its faults, Will Eisner's The Plot points the way to new ways of thinking about the form. Why shouldn't comix be used as a serious rhetorical device? Taking the medium out of the realm of pure narrative entertainment, Eisner's final work attempts the ultimate challenge of an artwork: something that will change the world. As such, it makes a perfect capstone to the oeuvre of one of comix' greatest forward-thinkers.