|

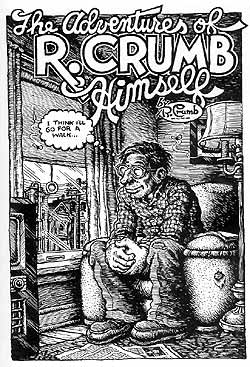

The appearance was organized to promote Crumb's latest book, "The R. Crumb Handbook" (MQ Productions; 438 pages; $25), a hardcover collection of Crumb's work over the years. Though it sounds redundant— everything touched by Crumb's pen, short of his ink stained sleeves, has been published already — this collection has great appeal to both Crumb neophytes and Crumb obsessives. Unlike other collections it is edited and designed, by Crumb's pal Pete Poplaski, as a kind of illustrated autobiography. Crumb provides commentary on his development as a person and an artist in passages interspersed with copious examples of his art and family photos. (A full multi-media package, it also comes with a CD of Crumb's recorded sessions with various amateur string and jug bands.) In a conversational style that frequently lapses into hilarious tirades against consumer culture, the media and any of a half dozen other peeves, Crumb reminisces about growing up as a child of 1950s suburbia through his later years as a museum-worthy "arteest" living in France. Always entertaining, "The R. Crumb Handbook" works as both an introduction to and enrichment of the author's work.

Crumb's appearance onstage at the New York Public Library made a striking contrast with Robert Hughes' paunchy ruddiness. Thin, with a full salt and pepper beard, eyeglasses and matted hair parted down the middle, Crumb wore a dark vest and suit jacket with a colorful tie and white shirt with an old-fashioned collar. The two explored Crumb's influences, contradictions, and the next big Crumb project, an illustrated version of the Book of Genesis. Highlights of the conversation:

Primary Influences

HUGHES: I want to know something about where your work begins from.

CRUMB: Well, there's the Egyptian hieroglyphs...

HUGHES: You didn't grow up looking at Egyptian hieroglyphs. What did you grow up looking at?

CRUMB: I'm a total child of popular culture. That's all I ever saw until I was 20 years old. TV. Comic books. That's it. In my family we had a TV when I was 5 years old in 1948. We started watching it a lot. We watched Howdy Doody and the Lone Ranger. That was the stuff that was deeply imprinted on me. Little Lulu and Donald Duck and Felix the Cat — real basic popular culture that was fed to kids. My parents had no culture. Not what's considered a culture with a capital K.

The Early Years

HUGHES: In your cartoons there's this character, very clean cut, straight, with a rigid suit. Is that your dad?

CRUMB: That's my dad, yeah.

HUGHES: In real life what did your dad do?

CRUMB: He was in the U.S. Marine Corps for twenty years. He joined in 1936. My mother made him retire in 1956. He loved the Marine Corps. He would have stayed if my mother had allowed him to. She made him quit because she got tired of being transferred around all the time and living in tract houses on U.S. military bases.

HUGHES: You were a base baby?

CRUMB: Yeah, I was a base baby. My father was that kind of man. That real classic, American John Wayne type of guy. A very intimidating man. Deep booming voice. A hot temper. If he got angry he might strike you.

HUGHES: Did he let you know that he loved you when he wasn't striking you?

CRUMB: No. He was from very reserved farm people. When I would come home to visit after I left home he would say, "It's good to see you Robert," and shake hands.

HUGHES: Did it ever cross his lamps that you would have ever ended up as an artist?

CRUMB: Well, we were always drawing comics as kids. My brother Charles made me draw comics. I was very much under his domination. He was actually a much stronger artistic visionary than I was. I had to do it to be a worthwhile person. And my father saw this and he used to say, "oh you guys will get over this when your reach your teens and you get out and play football." He was just totally bewildered by us. He saw us as Martians. We'd be lying on our beds in the fetal position, reading comics. He was a man of action, a U.S. marine. "Get off your duffs!" We broke his heart. He had three sons and they all turned out to be complete defective weirdoes. My older brother [Charles] committed suicide. He's dead. But my other brother [Max] is still alive. He lives in a hotel in skid row in San Francisco. He's lived in the same room for 25 years.

|

Crumb's Misguided Bid for Love

HUGHES: One of the reasons you've been so popular is because we think of you as fearless and crazy. You are one of the few Americans I have ever come across who seems to be totally unaffected by the notion of political correctness.

CRUMB: Maybe I should be more correct.

HUGHES: Why?

CRUMB: It's not nice to draw those pictures of women with no heads and those jiggaboo images of black people and stuff. I didn't realize how hurtful it was when I did it. I was surprised when people didn't love me after that. I want everyone to love me. Please love me.

HUGHES: Yeah, but you're the kind of loon who thinks that if he tells the truth about his own inner drives and if he exposes things, then people will love him.

CRUMB: Then they'll see that I'm human like them, and I just want acceptance.

HUGHES: But you see you're horribly wrong.

CRUMB: I realize that now. You can't make everybody love you. It's an exercise in futility and it's probably not even a good idea to try.

[A woman in the audience yells "We love you!" The audience applauds.]

CRUMB: Don't embarrass me. I know you love me, ok, alright. You're killing me you love me so much. Back off.

HUGHES: What I want to get to is the way these images worked on people. You have been furiously accused of being a racist.

CRUMB: Yeah well, [characters like Angelfood McSpade] were just stereotypical 1920s images of big-lipped black people which actually had very little to do with real African Americans. They were cartoon stereotypes I was playing around with. All that stuff I did in the late 1960s was cartoon stereotypes. I was playing around with them in a psychedelicized way. I dunno. It's hard to explain. It's not my job to explain it.

HUGHES: Well let's try to explain it. Why did practically nobody else get on to that very intense content and make something out of it the way you did?

CRUMB: I think that you had to be really, really alienated to get that point. You had to be very alienated from the culture.

HUGHES: Why is it that some artists will handle something that most of their audience would find reprehensible?

CRUMB: You've got to have nothing to lose. If you're trying to work the art game, if you're like Andy Warhol or something, then you're in with cake-eaters of society. You want to get in with them and please them and get their money.