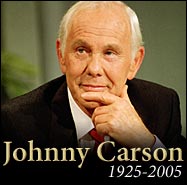

He started his job when Jack Kennedy was president and left it the year Bill Clinton was elected. For Americans in the second half of the 20th century he seemed to have been always around, and always would be. So I was sorry, and surprised, to hear on Sunday that Johnny Carson, king of The Tonight Show for nearly 30 years and more than 4,000 episodes, had died, at a reclusive, relatively youthful 79.

But the chorus of keening on TV news and variety shows threatens to extend the state mourning for this talk-show host to a Reaganesque six days. On CNN (your official site for the Carson reliquary), on PBS (The Jim Lehrer News Hour) and of course on NBC (where Carson's successor, Jay Leno, emceed a comely hour last night), the Grey Panther parade of Carson's octogenarian guests came, to pay a last homage to the man who had made their careers — and, only incidentally, to score rare face time on the medium that nurtured them. "His death," David Steinberg said of Carson on Aaron Brown's CNN show last night, "has been a boon to comedians who haven't been on TV for quite a while." On the same show, Esquire's Bill Zehme noted the procession of effusive tributes to this very private star, and added, "If Johnny were alive today, he would die."

|

||

|

||

What prolonged the media attention, other than the reach of the star's eminence and the need to fill air time in a slow news week, was the enigma of Carson. Millions saw and liked him 150 times a year, yet he steadfastly hoarded the essence of his personality. "If the conversation edges toward areas in which he feels ill at ease or unwilling to commit himself," wrote Kenneth Tynan, who interviewed Carson for a 1977 New Yorker profile reprinted in the book Show People, "burglar alarms are triggered off, defensive reflexes rise around him like an invisible stockade, and you hear the distant baying of guard dogs."

Anyone who watched Carson, studied him, as we all did, for decades, saw two things: the Univac brain, riffling through the comic possibilities as he listened to his guest, and an instant later ejected the perfect bon mot; and his distance from the action, as if he were watching the show and himself from some Olympian aerie, where it was always cool. Tynan writes of Carson appraising the other guests at a party, "his eyes twinkling like icicles." It was what we know, from Carson's avatar Letterman, as Midwestern cool: ingratiating but withholding.

Johnny knew his limitations — some called it shyness, others arrogance — and, naturally, bent it into a joke. "I will not even talk to myself without an appointment," he wrote in the late 60s. In lieu of interviews, Carson supplied all-purpose answers to journalists' probes: "Yes, I did"; "I can't answer that question"; and "As often as possible, but I'm not very good at it yet. I need much more practice."

Ten happy memories of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson:

1. Ed Ames throwing a tomahawk that landed near the groin (actually, in the inner right thigh) of a silhouetted figure on a board. Carson: "Welcome to Frontier Briss.'"

2. The early appearances of these young stand-ups: Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, Godfrey Cambridge, Joan Rivers. Each one smote a Philadelphia kid with the force of comic revelation. And each one, and a hundred others, vaulted from the Tonight Show spotlight into life-long careers, sitcoms, movies, a fame nearly as enduring as that of the host who cackled, winkedand gave the OK sign from his desk.

3. Paul Ehrlich, a biologist from Cal Berkeley, who in the early 70s became a superstar on Carson' show by predicting that the earth's population would be 12 billion by the year 2000. (Population in 2000: 6.5 billion.)

4. Autumn in New York and Moonlight in Vermont: Not only did the two tunes seem to run constantly through his head, but, he would say every few months, "They're the same song!" One night, a psychic asked him to think of any phrase, any phrase. I know what it would be, and it was: Moonlight in Vermont.

5. Art Fern: "Go to the Slaussen Cut-off, cut off your slaussen, get back in your car..." Art was one of the half-dozen characters Carson played over the years, and underlined the connection of this up-to-date show to the antique traditions of vaudeville, where the star would wear outlandish garb, leer at his voluptuous stooge, pirouette pratfalls — as Carson did once, with precision timing, onto his own (breakaway) desk.

6. Joe Namath, on the couch (but in a nice way) with a feminist author. Why should boy children be more desirable than girl children, she asked. Namath, plaintively: "But I want a little Joe."

7. Jim Fowler's (or Joan Embery's) wild animals, most of whom seemed unnaturally attracted to the host's hair.

8. The wedding of Tiny Tim and Miss Vicky: Carson's all-time highest-rated show featured the nuptials of an eccentric ukeleleist (whom I had seen perform in his early Village days) and a 17-year-old fan. The following week, Carson had a honeymoon joke: "There are already signs of trouble in the marriage. Last night Miss Vicky hung a sign on their hotel room doorknob that said: 'Disturb.'"

9. Desk gag: "McDonald's this week sold its one billionth hamburger. Why, do you realize that if all the meat in those burgers were stacked up, it would stretch to here?" — and he raises his hand a foot from the desk top. (McDonald's threatened to sue, not realizing it was goofy to demand a retraction for a joke.)

10. Monologue gag: "Ernest Borgnine and Ethel Merman were divorced, on grounds of irreconcilable faces."

He was good with 10 million people, lousy with 10. —Ed McMahon, to Jay Leno on Monday's edition of The Tonight Show

Born in Corning, Iowa, and raised in Lincoln, Nebraska, Carson found his calling when he read a magic book. He dubbed himself the Great Carsoni and quickly learned — or found within himself, the secrets of conjuring —misdirection, poise, timing, a commanding personality —which are also the secrets of standup comedy. His model was Jack Benny, the radio comedian. Benny could pull a laugh out of a sour audience with only a pause and a stare, which was pretty daring for an aural medium. Dick Cavett, who would later write for Carson and host his own talk show on ABC and PBS —and who at 13 saw Carson, then 23 and back from Navy service in World War II, perform in a Lincoln church basement —says that Johnny's thesis at the University of Nebraska was on Benny and the mastery of comic pacing. Was it called It's All in the Timing? That was the motto embroidered on a cushion that Tynan found in Carson's home office.

Disc jockey; writer and occasional performer on Red Skelton's CBS show, which for one night gave him the whiff of stardom when he substituted for the injured star; host of a short-lived interview show, Carson's Cellar, and a flop CBS skein, The Johnny Carson Show; then, in 1957, the gig that earned him fame, an ABC daily quiz program, Who Do You Trust? The Q&A portion of the show was negligible; it was Carson's fast, easy banter with his guests that got the attention of the NBC brass. Jack Paar, whose eventful reign as host of The Tonight Show had also begun in 1957, was itching to do a prime-time chat fest. The network courted Groucho Marx, Bob Newhart and others, but settled on Carson, who took over in the fall of 1962.

Paar had been hot, mercurial, no surer of what he would do next than his audience. If he'd tangled with NBC earlier that day, or if his daughter Randy got her first training bra, he blurted it out on the air. The show's intimate, neurotic tone made watching Paar an energizing, enervating experience —Event Television.. Carson established order, control (one of his favorite words), an elastic predictability. After the Paar boil, Carson, with his sang froid and what Tynan calls "his cobra-swift one-liners," brought a cooler temperature to Tonight. He seemed to verify Marshall McLuhan's dictum that TV is a cool medium, not for shouters but for soothers. (This was before Crossfire.) He was also a dry white wine in the sweet, gushy Manischewitz Concord Grape world of showbiz. Other comics might beg for love; Carson accepted the laughs, but, I'll bet, didn't need them to warm his needy heart. What need? Some would say, what heart? Remember that sang froid means cold blood.

Under Carson, The Tonight Show became Habit Television, which is how the sponsors like it, and most viewers too. Not everyone wanted the Paar caffeine jolt after midnight; what's needed is a pleasing comedy sedative. The ratings underlined the acuity of Carson's choice. After 15 years his audience had nearly tripled Paar's, and accounted for 17% of NBC's revenue.

Soon America got to know Johnny —what did I say!? We to know his mannerisms: the wink, which could be mischievous or genially conspiratorial; the spasmodically shrugging shoulders, a la Bogart (one of Carson's favorite and most frequent guests, Don Rickles, said the other night, "I thought he was a football player and the pads were too high"); and the sharp, brittle laugh, which was less an expression of mirth than a cue to the audience that his current guest had passed the test. This ha-ha bark was humanized by proximity to the warmer, manly, practiced guffaw of his announcer, Ed McMahon. But that was Ed's job: the designated laugher, his boss' exemplary yes man. (Literally, since he would add a Yes! to the laugh.)

Carson was easy to imitate (by Rich Little in the 60s, Dana Carvey in the 90s, with Phil Hartman superb as Ed), difficult to know. As McMahon once said, in a remark I find both delphic and profound, John packs a tight suitcase. Even those closest to him had trouble figuring out if they had pleased him, and some of them suffered when, without realizing it, they fell short. He fired his brother Dick from directing the show (Dick then directed Merv Griffin's daytime schmoozathon). He summarily canned Art Stark, who had produced Who Do You Trust? and, for its first five years, the Carson Tonight Show. He broke up rancorously with his agent-lawyer-manager Henry (Bombastic) Bushkin. He also divorced his first three wives. In an uncharacteristically revealing moment in the 60s, Carson said that a man has to choose, and realize, which is more important, his family or his job. For him, he said, it was the job.

He did fine at the job, earning himself millions each year, the network tens of millions. His negotiations with NBC won him a severely reduces work load, from 90 mins,. five times a week, 48 weeks a year, to an hour three times a week, 37 weeks a year, with reruns and substitutes filling the other slots. (By the end he was his own gust host.) But he didn't use the spare time for Manhattan or Beverly Hills partying. Working the room made him acutely uncomfortable. He was a loner who shrank from revealing his feelings, if he had them. Joanna Carson, Johnny's third wife, told Tynan she had seen her husband cry only once: at Jack Benny's funeral.

"The most annoying thing about Carson is his unwillingness to swing, to trust himself or his guests. ... He never looks at you; he's too busy (1) watching the audience to see if they are responding, and (2) searching the face of his producer for reassurance." —Rex Reed

He wasn't trying to swing; he was trying to steer. Steer guests into the studio audience's acceptance; steer the home viewer into responding as enthusiastically as the studio audience did; and steer the mass of viewers to advertisers. Helmsman may not be the word. Say, instead, salesman. The more people who watched — rather, who tuned in and didn't tune out because something affronted them or sailed over their heads — the more money the show, the network and Carson made.

He explained this to a 1977 group of Harvard undergraduates, one of whom had tiptoed toward the dumbing-down issue. "If you're selling hard goods — like soup or dog food — you simply can't afford to put on culture," he said. "Exxon, the Bank of America — organizations like that can afford to do it [by sponsoring 'Masterpiece Theatre' and other PBS shows of higher brow]. But they aren't selling hard goods, and that's what 'The Tonight Show' has to do."

As a cultural weathervane, Carson straddled two eras: the 50s and 60s, when all arbiters of popular taste, from a magazine editor to a comedian-host, were expected to pretend some interest in high culture; and the last 30 years, when those same custodians of taste were allowed, commanded, to express no interest. Readers of a certain age can recall when every New York Times music critic was writing about classical music, except for the guy on the jazz beat, and when opera divas graced the cover of TIME. (No rock performers were cover boys until the Beatles in 1967.) Now neither TIME nor Newsweek has a classical music critic, because neither magazine believes it has a need for one. They're just flying with the Zeitgeist.

So, over the decades, did Carson. In his very first Tonight monologue, on Oct. 1, 1962, he told the audience, "I'm curious," and he allowed his social and cultural curiosity fairly free rein. The young host would acknowledge that he attended the opera (his favorite: Giordano's Andrea Chenier). He booked serious authors to fill the last 15 mins. of his then-90-min. broadcast. His musical guests eschewed rock 'n roll; they included crooners, opera tenors and sopranos, lots of jazz men, both in the spotlight (Joe Williams must have sung Every Day I Have the Blues 40 times in those days) and on the bandstand, which was stocked with some of the best mainstream jazz musicians. Like Hugh Hefner, another essential taste-shaper of the period, Carson found that mixing esteemed authors and cool jazz with his staple entertainment (jokes for Johnny, Playmates for Hef) gave the enterprise a broader, higher reach.